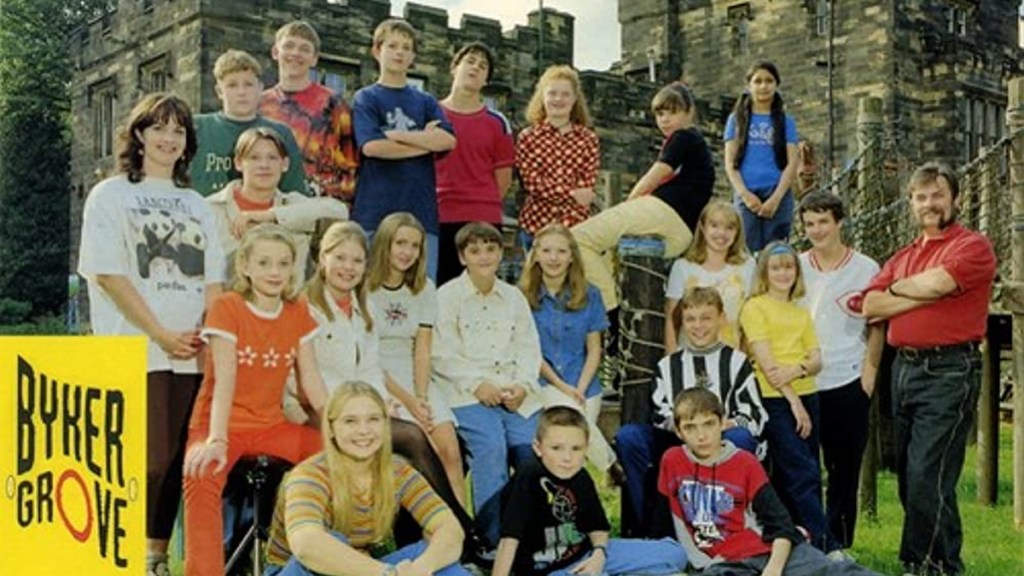

What do you do when the plug is pulled permanently on your TV show, with just a handful of episodes to go? How do you wrap up over a decade of storylines and characters in twenty-five minutes? How do you mark the end of an era? That was the dilemma facing the makers of Byker Grove, the occasionally-gritty teen drama about a Tyneside youth club when it was finally axed in 2006. The show had been a tea-time institution, running on BBC One every autumn since 1989 (launching the careers of Ant and Dec, Jill Halfpenny and Donna Air along the way.) The last episode of the eighteenth and final series went out on December 10th, fifteen years ago this week.

The show’s final story has gone down in history as one of the all-time bonkers meta TV endings. In the episode, titled ‘Deus Ex Machina’, the teenage Grovers learn that they’re characters in a TV show, manipulated for the entertainment of an omnipotent writer, who is bringing their story to a close. Now self-aware, the crew are given the ability to write their own endings by their creator, who can’t bear to kill them off himself. Much madness ensues, as the kids let their imaginations loose: the Grove is attacked by aliens, zombies and a T-rex, while one girl wears an “End is Nigh” sandwich board and begs for mercy from the “benevolent scribe” in the sky. At the end of the episode a pair of pre-teen anarchists, determined to keep the Grove out of the hands of evil property tycoons, push the plunger on a make-shift bomb and the screen is flooded with white light, after which a montage of characters from across the years plays over The Beatles’ ‘In My Life’. For a show that had previously concerned itself with teen sex, homelessness, soft drugs and that time Dec blinded Ant with a paintball gun, it was quite a big existential swing.

“You don’t want to end the story,” explains Bryan Johnson, the show’s final script-editor, who wrote the episode, “I love those characters and I got a bit obsessed with ‘what happens to my characters once nobody is writing them?’ So I thought I’d give them the chance to end their own story. The whiteout was the point where I’d handed it over to the viewer to create their own ending; if you want it to blow up, it’s blown up. If you don’t, someone’s pulled the wire out. There was no going back, but [for me] life would go on in their world.”

Matt Bloom, who cut his teeth directing Byker before going on to a career that has garnered a BAFTA nomination and an Emmy, remembers the moment the story was first mooted. “The producer and writer sat me down and pitched me the final episode,” he says. “There was a silence in the room, and my jaw dropped and I thought ‘this is fucking insane’ and then I thought … the audience is going to love it, I’m going to love directing it, the cast are going to get a kick out of it. Let’s do it’.”

In its own way, Byker Grove was genuinely iconic: it tackled big issues and generated genuine superstars and memorable TV moments, while always grounding itself in humour and playfulness. To those working on it, and those who had grown up watching it, Byker was important. By the mid-2000s, however, viewing figures had started to dwindle and interest at the BBC had faded dramatically. “They wanted to stop making teen shows.” explains Bloom, “they wanted to create the CBBC channel, just for kids stuff, six-twelve let’s say, and let EastEnders and Hollyoaks pick up the teens. They didn’t want Byker Grove anymore because it was too teen; too issue-orientated.”

“A lot of it came from a misreading of audience research,” says Johnson. “They asked some thirteen and fourteen-year-olds whether they felt programmes like Byker Grove and Grange Hill were for them, and of course they said no. They said they watched grown-up programmes like Friends, not Children’s BBC, but of course they still watched it, and of course they got something from the storylines; they learnt something.”

The creative team agreed to change tack for Byker’s eighteenth series in an effort to save the show. “We made a series that was stupid and fun” says Bloom, who was brought in to helm the run, “there was a Full Metal Jacket episode, and a Kill Bill episode; it was actually a really good show.” Johnson, too, was happy to push the boundaries. “We experimented with storytelling techniques,” he explains “and I think we did some interesting stuff. We got a BAFTA nomination for one episode. It was all breaking the fourth wall and talking to the camera. We did a flashback episode, we did one where the story was told from three different character perspectives.” Alas, it wasn’t enough.

Read more

“It wasn’t until we came to sit down to storyline the last four episodes that I was told that they really were the very last four episodes,” says Johnson. “The BBC had decided not to wait until we’d finished,” says Bloom. “They’d made a financial decision to cancel the show.” The team now had to find a way to close out not only Series 18, but the preceding thirteen years of storytelling, with no space to build up to a finale. “That’s the most insane thing, looking back now,” he says. “You went from Ken Loach, Mike Lee, Andrea Arnold, Shane Meadows-style socially realistic drama and then… BANG. None of you are real. You’ve got to fight for your existence.”

The Byker team were unlucky – it’s extremely rare to be cancelled mid-run on British TV. “It’s always afterwards,” says Russell T. Davies, probably the UK’s greatest authority on television drama and someone who knows a thing or two about finales. “You make your series and then go through this waiting period. If it does well you assume you’re probably fine, if it does badly you know you’re probably axed, but most shows will sit in the middle ground, and that’s very, very difficult. Being cancelled mid-run just doesn’t happen.”

Back when he was a jobbing writer working on soaps and dramas like Revelations, Springhill, Families and The Grand, Davies’ finales, by necessity, had to work as both a full-stop and an ellipsis. “With a lot of those cheap soaps, we’d quite carefully engineer a finale that could be either a cliff-hanger for the next series or could be a real ending” he says, “Families [the ITV daytime soap Davies inherited in the early 90s]ended brilliantly with the mother-in-law murdering her daughter-in-law, who had slept with the father-in-law. At the same time we had a character, Jackie, inherit ten million Australian dollars, so we were all ready for Jackie the millionaire in the next series. That could have run and run. Revelations [a late-night soap Davies developed for Granada in 1994] ran for two years, and both years ended with a murder that the murderer gets away with, which gave us something for the next series. We made sure they came to a climax, but you’d build in enough to come back.”

Davies enjoyed the sheer boldness of the Byker Grove twist (“actually that’s all about creativity – ‘Byker Grove belongs to everyone’ It was trying hard!”) but is not usually a fan of meta endings, describing such it-was-all-a-dream cop-outs as “like a writer masturbating. It’s a writer stuck at a desk thinking ‘this is fiction, so I’ll make it fiction, I’ll make my fiction their fiction.’ I think it’s wrong. It’s a fundamental breaking of the promise you’ve made to the audience. It undermines everything you felt and thought about those characters”. It’s why he thinks The Wizard of Oz has the “the worst ending in history … I was appalled by that ending. You wait for it to continue. Literally, as a child, you watch Dorothy wake up in the black and white world and there are all the avatars of the people from Oz, you wait for her to reach under the bed and pull out that pair of ruby slippers. It’s lacking a final moment. It’s shocking.”

Back in Newcastle, the Byker team had developed a punkish, fuck-it mentality (“There’s something about making a finale when a show has been cancelled that brings out a certain degree of nihilism” remembers Bloom), determined to give their baby a send-off that would be both memorable and make some sort of dramatic sense. Both Bloom and Johnson knew their TV history well enough to remember such meta loop-de-loops being tried before. Bloom references Seinfeld, Moonlighting and Sophie’s World while Johnson had in mind Spaced, The League of Gentlemen and the ‘Back To Reality’ episode of Red Dwarf, or even the occasional magical realism that had turned up on Hollyoaks and Press Gang – all shows that have turned in on themselves at some point.

Johnson also argues that the out-there ending wasn’t quite as removed from the tone of the show as people think. “Actually, Byker Grove did mad things all along,” he says “Duncan joined a religious cult! I think people misremember the early Byker Grove, they remember PJ getting blinded, they don’t remember PJ falling off a unicycle and dropping a tin of paint on Geoff’s head.”

In the end, both men are proud of the way they brought the show to a close. “Byker Grove fans who hadn’t watched the show in a decade were furious”, remembers Bloom, “but everybody of the right age loved it. It was a watercooler playground moment, and they thought it was just nuts. It was like the ending of Moonlighting was to me, those mind blowing endings that are really creative and lovely.”

“There were always good intentions,” says Johnson. “It’s always about serving the characters and the story. There was so much to pack in and tie up, and tying everything neatly seems too convenient unless you do something like this. If we’d been given more notice maybe we could have built up to it. But I’m glad that we had the chance to try something like this. I’m glad we dared to be different. We went out kicking and screaming.”