This article is sponsored by

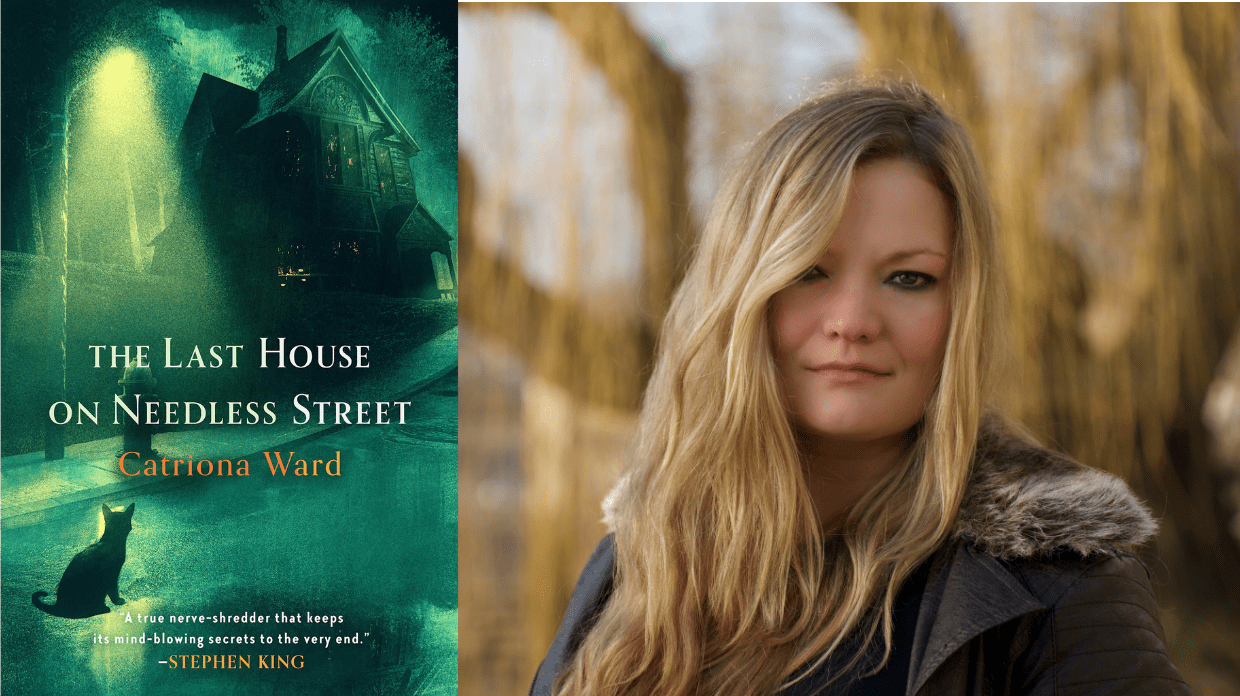

Catriona Ward’s latest novel, The Last House on Needless Street, is the sort of book that defies easy description and categorization. Part horror story, part mystery thriller, and part tragedy, the book subverts a lot of expectations about what a genre story should be and do, unpacking a complex emotional narrative in the midst of a menacing tale of fear, uncertainty, and constantly escalating dread.

“I’m not sure where it sits,” Ward admits with a laugh during a lengthy conversation with Den of Geek. “It’s a bit un-shelvable.”

To be fair, it was probably always going to be difficult to know precisely how to classify a story that heavily features a very religious talking gay cat, and that’s before you get to the potential kidnappings and possible serial murder of it all.

“The cat is a litmus test, isn’t it?” Ward laughs. “If you get parts of the talking cat in the second chapter, you’re probably going to enjoy the book. If you don’t, you may not.”

Especially since The Last House on Needless Street isn’t the sort of horror story (or even quasi-horror story) that relies on gore or jump scares to terrify its readers. Instead, its darkness is primarily rooted in more mental frights: Unreliable narrators, oppressively narrow points of view, and an almost unbearable tension lace through even the most basic scenes. Readers are left unbalanced by sequences they don’t entirely understand and can’t completely trust, armed only with “partial and imperfect knowledge.”

“One of my great loves is the Gothic, the fragmented narrative. The reader plays detective the whole time trying to piece together what is reliable and what is not,” Ward says. “There are all these oppositions in place. I think that’s something that horror and the darker side of fiction do very naturally anyway. I felt that this was just perhaps pushing the envelope a little bit further.”

Ward refers to her previous novels as Gothic-style stories of “distressed girls wandering about on moors,” and says that part of her drive to write Needless Street came from an “urge to do something completely different” and to “write something as mad as I liked.”

It’s safe to say that she has achieved that goal.

In the most basic sense, The Last House on Needless Street follows the story of Ted, a lonely man who lives in a boarded up house (on Needless Street, naturally) with his 12 year old daughter, Lauren, and his cat, Olivia. Children have been going missing at a nearby lake for some time and a woman named Dee, whose sister disappeared there some years prior, has convinced herself that Ted had something to do with it.

Whether he did or not, as well as the mystery of what happened to the “Girl with Popsicle” who vanished back then, are just two of the story threads this ambitious narrative attempts to balance as it juggles three different perspectives—one of whom is the aforementioned cat— and asks readers to question what they believe to be true and why.

“First person narrators for me are a much more realistic way of presenting the world than an omniscient, Godlike creator. You don’t get to know everything about everyone. You just don’t,” Ward says. “Your perceptions change every instant and quite often no two people remember the same event the same way. To me, that unreliability is incredibly lifelike, but I think it’s unnerving to people. I think it’s unnerving to the reader because fiction is supposed to be more organized than that. I think what I wanted to do with this [story] was destabilize that a little bit.”

The book embraces many of the most familiar aspects of the horror genre, but it also counts on its readers to possess a shared understanding of its common tropes and signifiers, and uses those assumptions to subvert many of their preexisting expectations.

“That was a decision,” Ward says. “To play [not just ] with the expectations of horror… but also with the snap conclusions people might come to about certain kinds of behavior or mental health conditions [or socio-economic indicators].”

The book’s narrative counts on its readers to feel as though they know what’s happening, that they’ve already guessed the twists ahead of them. And, as the story progresses, certain moments reinforce those assumptions. We’re afraid of Ted, because context clues say we should be, because our own knowledge of the world has shown us it’s often right to be suspicious of loner men who live in shabby, boarded up houses at the end of the lane.

And according to Ward, that unease is absolutely something she counted on her audience feeling. Because, although Needless Street has “no real factual content in the plot at all,” there are “echoes” of a real-life tragedy built into its bones, the kind that could certainly encourage readers to draw specific conclusions about the things they’re watching unfold.

“There are some deliberate reverberations that I set up with Ted in the beginning,” Ward explains.“He’s called Ted, and he lives in Washington state, near a lake where there had been a disappearance. I’m fascinated by the lake. Fascinated is the wrong word—I’m terrified, and the event that has quite a power over me is the Lake Sammamish Murders committed by Ted Bundy.”

In July of 1974, Bundy abducted and murdered two different women—Janice Ott and Denise Naslund—over the course of an afternoon at Lake Sammamish State Park. Despite the fact that thousands of people were at the lake that day, he walked up to each woman while they were with friends and introduced himself using his real name. Wearing a cast on his arm, Bundy asked the women for help. Each one walked away with him and was never seen again. Their remains were found on a neighboring hillside two months later, in such a state of decay that the local forensics team were driven to test the feces of local animals to help identify them.

“This is something that has made its way into my psychology and my imagination,” Ward says. “It’s an echo [in this story] because it’s such a landmark in my landscape of fear.”

The worst kinds of monsters, after all, are those that we can find evidence for in the real world.

“This absolutely horrifies me because what kind of world do we live in where someone can walk up to a woman in a group of friends, introduce himself by his name, and take her away and kill her in broad daylight?” she continues. “Twice in the same day. What kind of overpowering greed leads someone to need to do it twice in one day?”

For Ward, part of writing Needless Street necessarily involved processing “heartbreaking and often quite upsetting” things.

“It would be a bad book if I wasn’t afraid of it,” she says, explaining that there’s actually an important emotional element involved in telling and reading stories about our fears, of both the real and the fictional variety.

“I think horror doesn’t get enough credit as well for its redemptive qualities,” Ward continues. “The only reason I can write this stuff is because I’m afraid of it. And [there’s] actually a huge quality of empathy [involved] because what you’re saying to the reader is, ‘Here are my vulnerabilities. Here is what I’m afraid of. Are you afraid of it too?’ Then you’re forming this bond where you travel through the fear together.”

But, then again, by the time they reach the final page of Needless Street, readers’ ideas of what constitutes a horror story—and where precisely Ward’s book falls within the genre—may have changed. (And the author herself is well aware of that fact.)

“It’s a very strange genre, horror. Again, I don’t even know if this book is horror,” Ward admits ruefully. “This book is wearing the disguise of horror. I hope it’s [really] about survival and hope as much as it is about suffering. I thought that was really important to make sure that [those things] come out, [that[ it has the light shining through the dark branches as it were.”

The Last House on Needless Street is out September 28th. Find out more here.