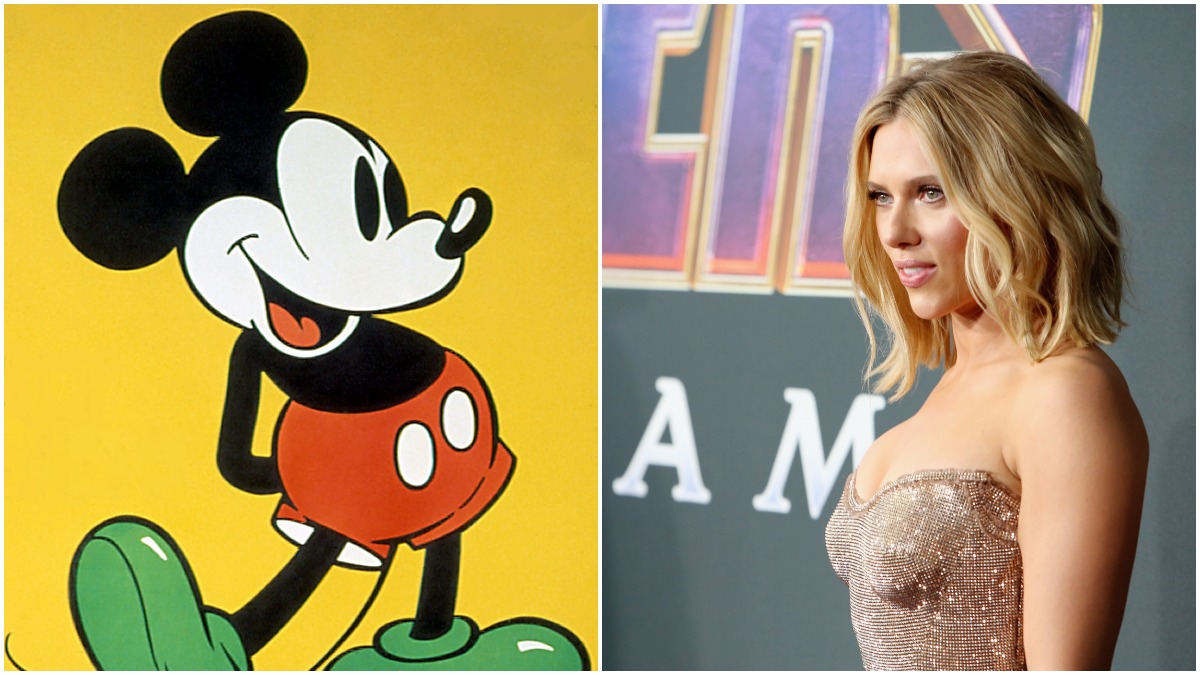

It was the shot heard around the internet: Scarlett Johansson, the star of eight Marvel Studios movies and the face of Disney’s biggest summer release, Black Widow, filed suit against Disney over an alleged breach in her contract. The immediate firestorm in the media—and more tellingly on social media—was intense.

Some have likened Johansson’s lawsuit to actors standing up to studios’ viselike control over contracts during Hollywood’s Golden Age (more on that in a bit); others have treated it as tantamount to betrayal of their favorite purveyor of superhero content. But perhaps no reaction was larger than that of Disney itself. While Johansson alleged she extracted “a promise from Marvel that the release of the picture would be a theatrical release”—thereby acting as the bulk of her salary due to the star having a profit participation clause—“[Disney] nonetheless directed Marvel to violate its pledge and instead release the picture on the Disney+ streaming service the very same day it was released in theaters.”

In addition to Disney’s public response being shockingly scathing, it also largely seemed to evade Johansson’s legal assertions. Instead the studio aggressively targeted Johansson’s character, seemingly shaming her for daring to bring up profits during such troubled times.

“The lawsuit is especially sad and distressing in its callous disregard for the horrific and prolonged global effects of the COVID-19 pandemic,” wrote the company which reopened its theme parks in July 2020. The response also went on to note Johansson already earned $20 million in upfront salary on the film.

The intended effects of these criticisms were clearly to vilify a star who headlined Disney’s biggest franchise of the last decade and cast a cloud of suspicion around her in the courtroom of public opinion. Any perusal of Twitter these days will show its effectiveness. Or as a statement from Women in Film, Los Angeles, Reframe, and Time’s Up accurately noted, “[Those criticisms attempt] to characterize Johansson as insensitive or selfish for defending her contractual business rights. This gendered character attack has no place in a business dispute and contributes to an environment in which women and girls are perceived as less able than men to protect their own interests without facing ad hominem criticism.”

The fact that those criticisms have been so effective at swaying public opinion, particularly in the fan community who is largely most concerned with the accessibility of the next Marvel movie, is as disheartening as it is distracting. Because what’s at stake here is more than Johansson’s ability to receive any sort of percentage on the revenue Disney is generating from its $30 “Premier Access” paywall; rather it’s the entire talent pool of the moviemaking industry trying to find out where they stand in a marketplace that is increasingly transitioning to streaming, come hell or high water.

The full ramifications are only starting to become apparent. Or as THR editor Matt Belloni broke in his newsletter over the weekend, after Johansson’s lawsuit, and after Cruella became the first live-action 2021 film that Disney unceremoniously put on Disney+, star Emma Stone is “currently weighing her options” in terms of suing the House Mouse. According to the same source, Emily Blunt might also be considering similar action depending on the current rollout of Jungle Cruise. Meanwhile Dwayne Johnson was conspicuously enthusiastic on social media about Jungle Cruise’s box office performance this morning.

These early cracks in what could quickly become a PR nightmare for Disney signal a battleground that’s been approaching the industry ever since WarnerMedia announced Wonder Woman 1984 would be released in theaters and on HBO Max last Christmas. At the time, Warner Bros. allegedly paid both Gal Gadot and director Patty Jenkins undisclosed eight-figure sums to offset the loss of theatrical profit participation they would’ve earned had Wonder Woman 1984 opened under normal circumstances. However, when WarnerMedia in the same month shocked the industry with the unilateral decision to release their entire 2021 film slate in the day-and-date format simultaneously, the blowback was fearsome.

That’s because in addition to damaging filmmakers’ artistic vision for movies designed specifically for the big screen—Dune director Denis Villeneuve even wrote a passionate op-ed about it—the decision completely upended the way talent earns money off studio films. Yes, this includes stars with $20 million upfront paychecks, but it also affects below-the-line people too.

“It creates a financial nightmare,” Judd Apatow told Variety last year about the now quaint seeming WB/HBO Max deal. “Most people are paid residuals—they’re paid back-end points. What they get out of it for years and years of hard work is usually based on the success of their films. And so now what does it mean to have a movie go straight to streaming? How do they decide what to pay you? Do you have a contract that allows you to negotiate, or is it really just up to them at this point? It raises thousands of questions, which I’m sure are very complicated.”

We’re now seeing those complicated questions spill over into the courtroom. For all the tumult WarnerMedia unleashed by blindsiding their talent with last December, the company has spent months trying to untangle the damage for at least A-list talent, signing undisclosed and fiscally hefty deals with stars and filmmakers ranging from The Suicide Squad to The Little Things. Apparently the studio is still in negotiations with Legendary Pictures for all the money the production company could stand to lose from a muted theatrical release of Dune in October.

But Disney, according to Johansson and her talent representation at CAA, has strikingly not made any such overtures to their A-list talent being blindsided by Disney+ reshuffles. Which in turn raises the question if that’s how they treat Oscar winners like Stone, and longtime franchise stars of billion-dollar Disney franchises like Johansson, how do they treat the below the line people who can’t afford to publicly take this to court?

What we are seeing is a debate over what role the actual creative talent behind the films you love has in profit-making in the 21st century. Disney has been at the forefront among Hollywood studios in cultivating a direct-to-consumer model via Disney+, and yet even when they add a luxurious surcharge like $30 on top of that subscription model, they are treating it as separate from the older system of how talent along all tiers is paid.

So Johansson stars in Black Widow, which has the biggest box office opening since the pandemic began with $80.4 million. But as Disney crowed that same weekend, the studio made another $60 million on Disney+ surcharge fees, which is likely worth more than the $80.4 million box office bow after theaters get their cut—and that $60 million came at the expense of theatrical tickets, particularly when easy access to HD pirated copies of Black Widow are factored in. Hence how even though the Marvel movie opened bigger than F9, the theatrical-only Vin Diesel movie has earned about double what Black Widow did at the global box office.

Currently, Disney is saying Johansson—and by extension anyone else with a residual deal—should not be able to dip into that $60 million revenue from the opening weekend…. even though at least in Johansson’s case she was contractually promised an exclusive theatrical window.

In many ways, this mirrors the 1980s and ‘90s home media boom from first VHS and then DVD. It created a whole new revenue stream for Hollywood in the home media market. As Matthew Belloni has also noted in his latest newsletter, talent agencies like CAA are all too aware of how stars were shut out of the home media market which, for a time, doubled or even tripled studios’ profits. Now the streaming revolution has come, and talent is not keen to see that happen again.

Johansson being a big enough star to actually be the first to refuse to rollover on this is, indeed, reminiscent of Olivia de Havilland in Hollywood’s Golden Age. In 1943, de Havilland was at the end of her seven-year contract with Warner Bros. and a contentious relationship with WB head Jack Warner. Despite becoming a star under the WB system, de Havilland’s biggest successes were when she was loaned out to other studios—as WB controlled her career under an ironclad contract, as was pro forma at the time. Meanwhile in WB movies, de Havilland was often cast as a thankless love interest. As her star stature rose, her willingness to turn down many of these roles grew. As a consequence, Jack Warner suspended de Havilland for six months and, at the end of her contract, revealed the studio expected her to stay on the WB lot for another six months to make up for lost time and revenue.

De Havilland sued Warner Bros. in the same Los Angeles County superior court Johansson has now filed suit against Disney, and after a successful litigation and WB’s subsequent appeal failing, “the De Havilland Law” essentially ended a studio’s ability to control stars’ lives and careers like they were pampered indentured servants. In response WB attempted and failed to blacklist de Havilland.

It appears that once again, Hollywood is on the precipice of a turning point.