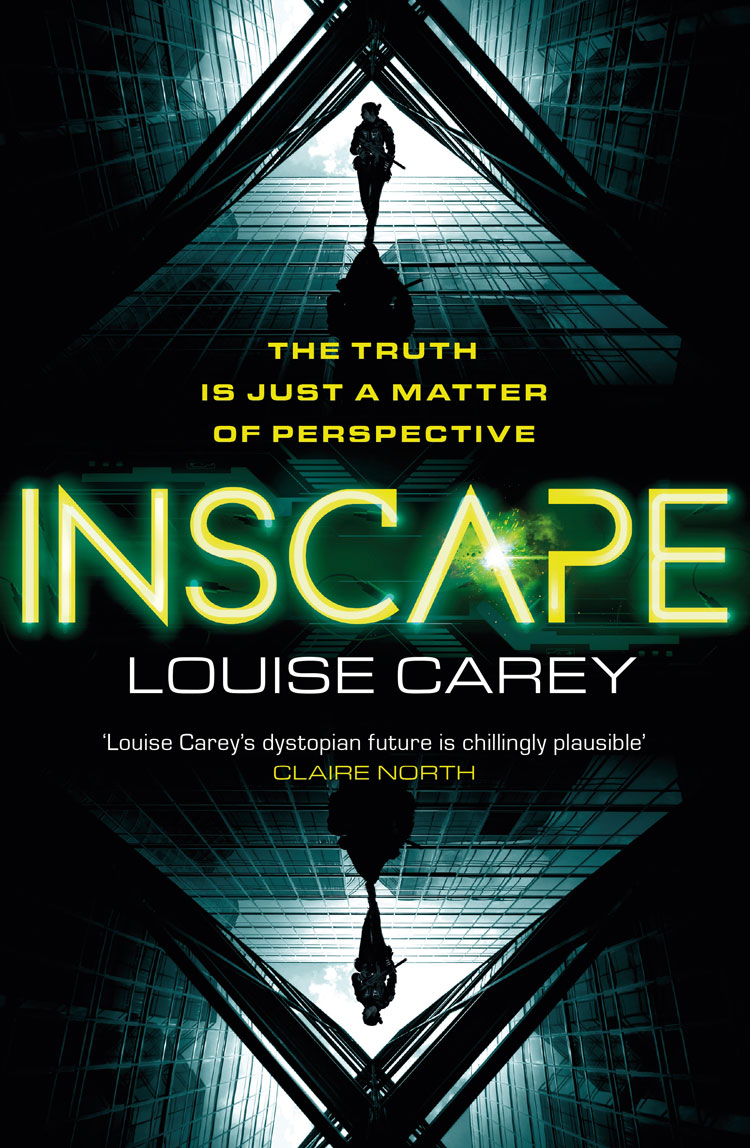

Inscape follows rookie agent, Tanta, who has trained her whole life to work for InTech, one of the big corporations who run the city. Her very first mission is a code red: to take her team into the unaffiliated zone just outside InTech’s borders and retrieve a stolen hard drive. It should have been quick and simple, but a surprise attack kills two of her colleagues and Tanta barely makes it home alive.

Determined to prove herself and partnered with a colleague whose past is a mystery even to himself, Tanta’s investigation uncovers a sinister conspiracy that makes her question her own loyalties and the motives of everyone she used to trust.

We speak to Inscape author Louise Carey about psychopathic corporations, the next evolution of technology, power dynamics and mind control…

When did you first have the idea for Inscape?

Waaay back in 2015. I wish I had an interesting story about how I came up with it, but the reality is that it just popped into my head one day. The seed that started the whole thing was the Inscape technology itself, and a sense that the novel would be set in a society run by big corporations; everything else grew from that. I’d decided on those elements — and the title — long before I settled on a cast or a plot, which both came relatively late in the process. In my earliest notes on the book, it was going to be a much slower, quieter story, with a smaller cast — not a thriller at all.

What were your inspirations when writing Inscape?

I’m sure there were lots, but the one that stands out to me the most is the fantastic cyberpunk anime PSYCHO-PASS. It’s set in a hellishly dystopian Japan where an authoritarian government polices its citizens’ mental states. Like Inscape, the show is built around a pivotal piece of new technology —in this case, a smart gun that scans the mind of whoever it’s aimed at and shoots with varying degrees of lethality depending on their propensity towards antisocial behaviour.

What stayed with me about the show is the way it dissolves the boundary between public and private. The protagonist of PSYCHO-PASS has adapted to live in a world where the most secret, sacred thing about her — her own mind — is constantly subjected to state scrutiny. It’s a harrowing watch, and the questions it raises about surveillance, big data and identity fed into Inscape in a big way.

Inscape paints a picture of a world where cities belong to tech giants. Did you model the two opposing companies on any particular real world companies?

I didn’t have any particular companies in mind when I wrote the novel, but I was thinking about big corporations in general, and especially how unethically some of them behave when they think they can get away with it. Boeing tried to conceal the design flaws in the 737 MAX, even though doing so led to hundreds of deaths. Disney is withholding royalties it owes to Alan Dean Foster and other authors, despite those payments being a drop in the ocean for a corporation of that size. I have a lot of time for the idea that corporations are, essentially, psychopaths. That’s what I find chilling about the world of Inscape: it’s run by entities that don’t have the capacity for empathy or remorse, and whose motivations are purely selfish.

The fact that the corporations in the book are tech giants adds another dimension to the story. We already live in a world where big tech companies know a disturbing amount about us as individuals; Inscape builds on that.

Where did the idea of the Inscape technology come from and how did you decide on its capabilities and limitations?

To me, the Inscape system feels like a logical evolution of the smartphone. A lot of effort goes into making our devices ever more portable and convenient — wouldn’t carrying them around in our own heads be the apex of that drive? Elon Musk’s Neuralink start-up is a step in that direction already, with its ambition to create technology that can interface directly with the human brain.

When I was planning out the capabilities and limitations of the tech, I was thinking about what was necessary for the plot, but also about verisimilitude. I went to a panel about this at SFX BookCon a couple of years ago, where Tade Thompson said that in order for a piece of technology to feel realistic, it must sometimes break. In real life, nothing works perfectly all the time. I found that insight very helpful.

Did you map out the history of how the world got to the point it is in Inscape?

Only in very vague and general terms! I have my own thoughts about what happened during the Meltdown but given the events of 2020 (and 2021 so far), I’m glad I didn’t spell them out too explicitly in the novel itself. There’s a very ending-of-days feel to world affairs right now and as is often the case, the truth is stranger than any fiction I had planned.

As a fiercely independent and capable YA hero, how important was the portrayal of Tanta’s relationships with Reet and Cole?

Those two relationships are central to the book, and to the trilogy as a whole. Tanta’s friendship with Cole came first: it was present from the earliest drafts of the novel. I liked the idea of writing about a friendship between an older man and a younger woman, with no elements of romance whatsoever, and making that central to the book. It’s not a dynamic I’ve encountered very often in my own reading, so I thought it would be interesting to explore it.

I’ve seen and read a lot of stories where relationships between (sometimes much) older men and younger women evolve into romances. I don’t have an inherent problem with that trope — I’ve seen it done both well and badly — but I think on some level the power dynamics involved often trouble me. I wanted Tanta and Cole to be equals. They have different skillsets, and at various points each of them is forced to rely on the other for help, but their friendship is based on mutual respect.

Tanta’s romantic relationship with Reet developed more slowly in my planning of the book, but ended up being just as pivotal. Tanta is both stoical and good at disguising her feelings; Reet is the one person who can see through her façade, but also the only person Tanta trusts enough that she’s willing to be vulnerable with her. In that sense, Tanta’s scenes with Reet allowed me to present her in a very different light to the way she appears in the rest of the novel.

Some people have their bodies taken over to conduct menial tasks like the sleepers and the conduit. What were your thoughts and inspiration behind this idea?

I was thinking about the way a company owns its workers’ time while they are at work. Ideas like the utterly toxic concept of ‘time theft’ have created a workplace culture in some businesses where it’s almost like you belong to the corporation from nine to five.

Work contracts that police employees’ behaviour and speech outside of office hours extend this sense of ownership and entitlement even further. I think the sleepers in Inscape are me taking some of those concepts to an extreme.

How did you find exploring the morality and ramifications of using mind control?

It’s one of the aspects of the book I enjoyed writing the most. I was studying for my MSc in Psychology when I started planning Inscape, and many of the concepts I was learning about found their way into the book in various shapes and forms.

What particularly interested me is the fact that the mind isn’t a single entity. What we think of as the mind is really a huge number of complex and interrelated systems: cognition, emotion, memory, etc. Without giving too much away, in Inscape I was interested not so much in mind control as a whole, but in what might happen to people if one aspect of their mind was being manipulated. What would your experience of the world be like if a corporation could edit your memories? Or periodically turn off your consciousness, as with the sleepers? Inscape explores some of those ideas.

What are you reading right now?

Bram Stoker’s Dracula. As a former English lit student, I’m finding it fascinating. It’s a book that’s obsessed with the idea of written records: it’s told through a series of diary entries, letters and newspaper clippings, and characters are constantly going back and re-reading the things they have written to move the story forward. I think the real hero of the novel is probably the typewriter.

Next on my list is The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison.

What’s next for you?

I finished the second book in the Inscape trilogy during the lockdowns last year; now it’s onto edits, and then book three! After that, who knows? But I hope it will involve more writing, in one form or another.

Inscape by Louise Carey is out now from Gollancz.