The setting of David Fincher’s Mank largely resides in the confines of Herman J. Mankiewicz’s bedroom and its surrounding desert vistas. The man who is about to pen what many consider the bible for the greatest film ever made was sent there—banished, really—by Orson Welles in order to keep a low-profile from the Hollywood press, and to keep “Mank” out of boozy trouble. Thus his North Verde ranch is a location of moody interiors and desolate skies, and it’s framed by Fincher with the kind of reverence one might expect for an actual bible.

It’s not hard to guess why Fincher feels this way. This is the site, in Mank’s telling, of Citizen Kane’s genesis: the birthplace of a movie which has been declared twice by the American Film Institute to be the greatest film ever made, and which in 1941 was revolutionary. Indeed, early in Mank, Welles associate John Houseman frets the script is too confusing for a commercial audience to follow: a “hodgepodge of talkie episodes, a collection of fragments that leap around in time like Mexican jumping beans.” He doesn’t believe Mank’s insistence that a narrative can be a circle instead of a straight line; that a man’s life, even in caricature, is best conveyed via vignette.

If Fincher’s Mank takes anything significant in its presentation from the actual Citizen Kane, surprisingly it is that sentiment toward structure. Mank doesn’t seek to reduce the life of one of Hollywood’s greatest scribes to a few hours. Yet through the framing device of Mankiewicz, played by a cantankerous Gary Oldman, dictating his masterpiece to a secretarial Mrs. Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), flashbacks provide context to the man, and seem quizzically more reliable about facts than Mankiewicz’s present, still drunken circumstances. These elliptical insights intercut with Kane’s origin story, making narrative a circle and Mankiewicz a figure of staggering presence and immense self-loathing… in no small part because his masterpiece is stitched from acts of betrayal, then and now.

Owing more to Pauline Kael’s controversial (and somewhat discredited) “Raising Kane” essay than the actual Citizen Kane film, Fincher’s Mank takes the contentious position that Welles didn’t write any of the masterpiece that won him a screenwriting Oscar alongside Mankiewicz. In fact, he wasn’t even in the room when Mank dictated the film’s contents to paper, like a prophet revealing the word of God.

Rather Fincher, as well as his late father Jack Fincher, who wrote the Mank screenplay in the 1990s, prefer to penetrate the Welles “boy genius” myth—defying the general perception that Welles alone invented everything great about Kane at the age of 25. The Finchers are instead consumed with shining a light on Mankiewicz, plus the influences and regrets that drove him to pen Kane as an act of revenge against former friends and benefactors like old newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and his younger movie starlet girlfriend, Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried).

In this sense, Mank luxuriates in the written word to a greater degree than any Fincher film since The Social Network. With a highly literate script, Mank takes on the rapid-fire cadence of an early 1930s talkie, the type the real Mank cut his teeth on a decade before he holed up in the Mojave Desert. As a member of the fabled “Algonquin Club” of writers during the ‘20s, Herman was among the first of the New York playwrights and theater critics to sell out and move west, taking the lucrative paycheck of Hollywood work. He got rich but, in the mind of him and his contemporaries, sold his soul to mediocrity beneath his talent.

Even if he did, Mankiewicz contributed to some of the greatest comedies ever written, and had a hand in several Marx Brothers movies, including Monkey Business and A Night at the Opera—until he was fired off the latter by Irving Thalberg for his drunkenness. Mank picks up on the real Mankiewicz’s sensibility that words are weapons, as well as aphrodisiacs. The movie even suggests Mank betrayed his wife “Poor Sara” (Tuppence Middleton) entirely through witty repartee with Seyfried’s Davies. But betrayal is something Mank is acutely aware of given he was Davies’ favorite guest to San Simeon, a castle-like estate the wealthy Hearst holds court at with Marion. Mankiewicz was always invited to play court jester.

It’s at these parties that Mank gets the idea to turn his pair of hosts, particularly Hearst, into the tragic figures at the heart of Citizen Kane. And for the first time, Mank offers a concrete rationale for Mank’s double-cross, rooting it in a sober look at Old Hollywood that is absent the glossy romanticism so many other modern productions indulge. Mank’s Hollywood is a dream factory of deep shadows, but the kind that loom from base capitalistic greed and union fights; not epic noir nihilism. There is something more simplistic, and utilitarian, about the blackness here.

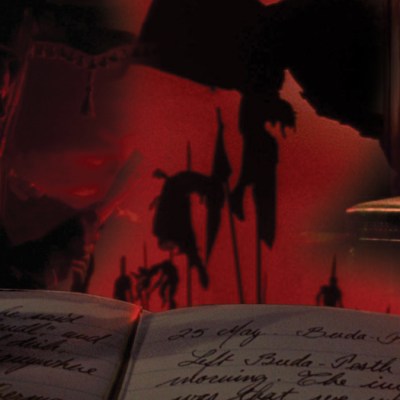

With the exception of some Welles-esque flourishes at Hearst’s San Simeon estate, and inside the much more dreamlike pressure cooker of the North Verde desert, Fincher visually eschews Citizen Kane and its mythmaking. This may even be Fincher at his most restrained, as the director evokes a traditional Hollywood approach to storytelling. He and cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt shoot the film almost entirely at eye-level, and seem more interested in the visual tricks of a Val Lewton horror movie or, occasionally, a Busby Berkeley musical. Fincher even marries them, with superimposed images of overflowing champagne glasses haunting Mank’s vision as he finds himself surrounded by enemies at a Republican Party gala on election night.

Read more

That gnawing sense of phoniness, and the more intangible dread of unrealized potential, informs Oldman’s irresistible performance. Another doughy lush of a protagonist for the actor after Winston Churchill, Oldman nevertheless finds an irresistible charm in Mankiewicz. He’s like an overgrown child who’s perpetually distracted but never bored. He’s quite pleased to stare off into space and soak up every loathsome detail about those around him, waiting at the chance to pick at his acquaintances’ foibles like a brat ripping at the wings of flies. Oldman anchors the movie with such negative, contrarian energy that it doubles back to become endearing.

The rest of the cast is uniformly perfect, as one would expect from a Fincher film, but Seyfried is the standout with her thick Brooklyn accent. Like Oldman’s Mankiewicz, one suspects she is more aware of the artifice around her than she lets on. But her devilish self-absorption is more than willing to be content with Hearst’s idle games. She might even convince some she’s happy in them, if not for Marion’s continual draw toward Mank. Whispering her and Hearst’s secrets to this self-destructive screenwriter, Marion comes across like the cat who enjoys walking beside the bulldog’s fence.

Interpretations like this of Davies, and by association Dance’s falsely congenial Hearst, breathe humanity into the marble statues that Welles and Mankiewicz imagined as Charles Foster Kane’s Xanadu. It also adds yet more texture into the contested origins of Citizen Kane.

Whether or not Welles deserved co-screenwriting credit for his most famous work is something worth debating, but Mank is entirely correct to point out that he gets more credit than he should in the age of auteur-worship. Mankiewicz was from a different generation of New York writers, one with a more playful and cynical disposition than even Welles’ fabled Mercury Theatre. David Fincher and his father offer a stirring tribute to this oft-forgotten era.

Barring some minor personal quibbles about using digital HDR cameras in what is a love letter to classic film—as gorgeous as Mank is, its facsimile of celluloid remains just that—this is another masterful experience from Fincher that will reward repeat viewings. There is a dense attention to detail and structure that is the hallmark of all of the director’s movies, but what makes Mank the true rare thing is its affection for its protagonist. It’s refreshing for Fincher to love his subject, even if none of the other characters, including Mank, can.

Mank opens in select U.S. theaters on Nov. 13. It premieres on Netflix worldwide on Dec. 4.