There’s a time and place in my life for a cosy fantasy! But my heart will always belong to the stories that use fantasy to explore the darkest, ugliest parts of our world — before giving us that moment of catharsis that lets us believe that it doesn’t always have to be this way.

Damsel, by Elana K. Arnold

“When the king dies, his son the prince must venture into the gray lands, slay a fierce dragon, and rescue a damsel to be his bride.” But when Ama awakens after her rescue in the kingdom of Harding, with no memory of the past, she realises her new fairytale life is a gradually constricting nightmare where nothing is as it seems. Arnold’s depiction of the claustrophobia and terror of coercive, misogynistic control makes this one of the most upsetting books I’ve read. But oh, the payoff! It’s worth the suffering for that one climactic moment, I promise.

Juniper and Thorn, by Ava Reid

This retelling of the Grimm Brothers’ fairytale The Juniper Tree doesn’t shy away from delving into all the elements that were present in the original, including child abuse, cannibalism, and murder. This book will make you viscerally understand why domestic abuse is also called intimate terrorism. But Reid never puts a foot wrong as a storyteller, and ultimately leads us on a path of escape where nothing is fixed, but healing is possible.

Nettle and Bone, by T Kingfisher

“This isn’t the kind of fairytale where the princess marries a prince. It’s the one where she kills him.” Marra is sick of watching her sister suffer at the hands of her abusive prince husband, and mounts a rescue mission. Kingfisher’s books acknowledge the darkness of the world — and then matter-of-factly remind you that there will always be ordinary people with pragmatism, good humour, and a willingness to roll up their sleeves to battle injustice. I’ve never once finished a Kingfisher story and not felt hope.

The Woods All Black, by Lee Mandelo

This Appalachian period novella explores small town religious bigotry, reproductive justice and bodily autonomy, and the absolute necessity of fighting to live who as you truly are. Mandelo doesn’t pull any punches, including in his delivery of PEAK queer revenge. If you don’t absolutely howl with schadenfreude at the ending, I don’t know what to do with you.

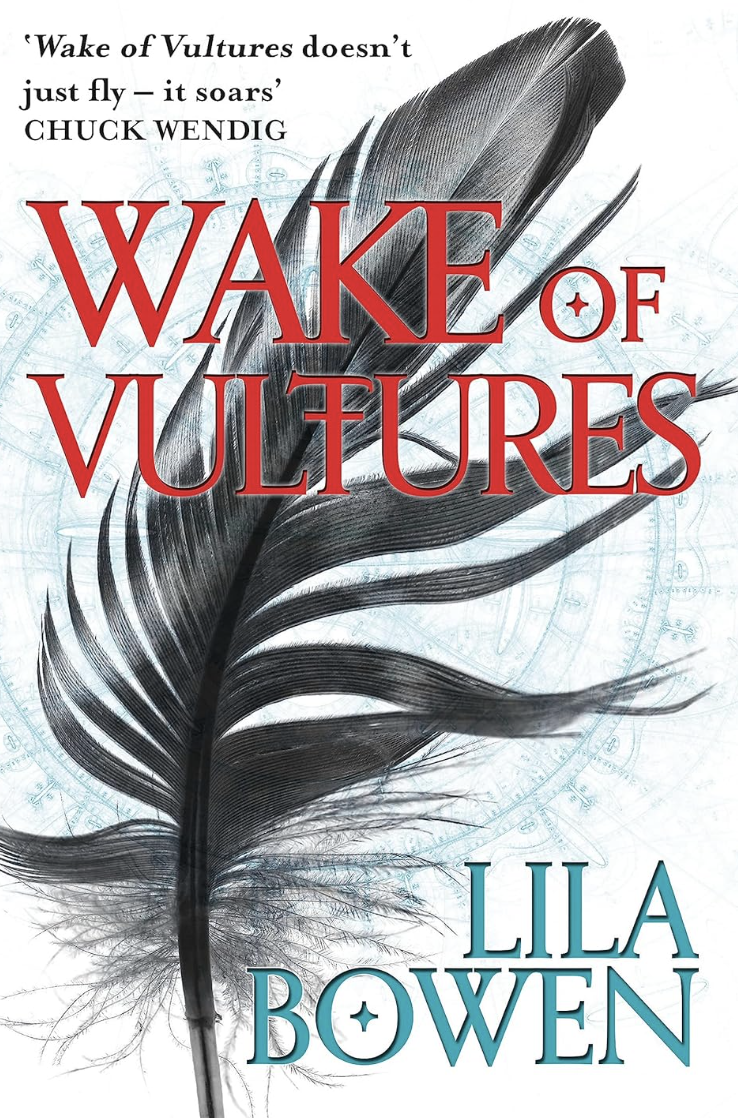

Wake of Vultures, by Lila Bowen

This definitive entry in the ‘weird western’ fantasy subgenre from a few years ago delivers us into an unsentimentally brutal world of cowboys, gods, and gruesome monsters. Bowen doesn’t shy away from depicting just how grim this world can be for her enslaved, mixed-race, trans protagonist. But it’s the story’s empathetic exploration of intersectional identity, and its grounding in native folklore, that really set this one apart from the white-protagonist classics of the genre.

Shelley Parker-Chan is an Asian-Australian former diplomat and international development adviser who spent nearly a decade working on human rights, gender equality and LGBT rights in Southeast Asia. Named after the Romantic poet, she was raised on a steady diet of Greek myths, Arthurian legend and Chinese tales of suffering and tragic romance. Her debut novel She Who Became the Sun owes more than a little to all three. In 2017 she was awarded an Otherwise (Tiptree) Fellowship for a work of speculative narrative that expands our understanding of gender. She lives in Melbourne, Australia, with her family.

He Who Drowned the World is out now from Mantle Books. Find out more here.