The Eighties saw the broadcast of some of the finest Doctor Who stories ever, but unfortunately some of the poorest too (occasionally next to each other in transmission order). It was extremely inconsistent for the most part, settling down towards the end of its run as the Seventh Doctor era tried a few things that the show would be lauded for upon its return in 2005.

There was definitely something there, but the show had already been mortally wounded. Rather than being formally cancelled, Doctor Who was quietly abandoned before renewed interest around its 30th anniversary in 1993 saw an attempted anniversary special (‘The Dark Dimension’) and the Children in Need mini-episodes ‘Dimensions in Time’.

A frustrating end, then, to a frustrating decade, but occasionally the potential of the show was tapped to produce stunning images, performances and concepts that have stood the test of time. This is another best-of selection where we were spoiled for choice, despite the lesser reputation of the decade.

10. Paradise Towers (Season 24, 1987)

Written by Stephen Wyatt. Directed by Nicholas Mallett.

In which the Doctor and Mel arrive at the titular towers to use the swimming pool, only to discover the residents have formed gangs, the pensioners have found a new food source, and the cleaning robots are going to the root of the litter problem.

Kroagnon, the Great Architect, ultimately hating the people who live in the buildings he designed is an idea of almost inverse subtlety to Richard Briers’ performance of the character: a critique of modernist architects and the kind of government that actively resents having people to serve people? In a garish children’s pantomime? Really Stephen Wyatt, you’re spoiling us.

The metaphor used for Season 24 is that it’s an attempt to turn around a speeding ship, fighting against the inertia of the previous seasons and the BBC’s reduced fondness for the show. The child-friendly tone that was imposed definitely shapes ‘Paradise Towers’ into a more pantomime package, with some very middle-class girl gangs and Richard Briers (playing the Chief Caretaker) clearly not taking the show seriously.

With ‘Paradise Towers’ the tone overrides the content for a lot of viewers: here is a story about contemporary housing issues (the tower blocks of the Sixties, people sold a dream that turned sour very quickly and was festering twenty years later) and cross-generational clashes that was influenced by the work of J.G. Ballard (specifically his novel High Rise, later adapted for film by Ben Wheatley and Amy Jump). It’s also got absolutely no continuity references, which was a significant departure for the show on broadcast, and it also seems to be on the side of the working class (or at least a 1987 CBBC version of the working class). It’s a show realising that it cannot simply aim itself at its own fandom if it wants to survive.

The clash between a big, bright children’s show and social critique actually works, indeed the gap between the angry ideas being expressed and the world populated by picture book illustrations is like someone commissioned Babette Cole to adapt The Atrocity Exhibition. This actually makes it grimly amusing rather than merely bleak, and there’s a Roald Dahl-esque horror to concepts like nice old ladies who turn out to be cannibals, or getting dragged down the rubbish chute to your death, or the recurring visual motif of a dead limb sticking out of the cleaning robot’s bin indicating who’s just been killed. Considering the production team were told they had to make something child friendly, it’s very funny that they managed to smuggle all this in just by making the tone ostensibly so.

9. Revelation of the Daleks (Season 22, 1985)

Written by Eric Saward. Directed by Graeme Harper.

In which the Doctor and Peri arrive at Tranquil Repose to pay respects to an old friend. Tranquil Repose holds dead bodies and minds in suspended animation, awaiting a cure for whatever killed them. Unfortunately Davros, creator of the Daleks, has taken up residence and is calling himself ‘The Great Healer’.

Writer Eric Saward plays to his strengths here: he enjoys writing for amoral, twisted characters and dialling up the black comedy. Based loosely on Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One, ‘Revelation of the Daleks’ spends its first half introducing its characters of disgraced knights, shady businesswomen, emotionally turbulent staff, Clive Swift somehow playing a total dick realistically, and then getting them all in the same location; it then spends its second half having them kill and betray each other. There is also a change in Davros, who at some point between ‘Resurrection of the Daleks’ and this, has watched the Matthew McConaughey bit in The Wolf of Wall Street. The end result is like the most violent episode of The Apprentice you’ve ever seen, and also the funniest story Saward has written.

There are also, arguably, two penis jokes. This is the most in a Dalek story not written by Steven Moffat.

While the focus is mostly on the guest characters, Saward does give them all clear motivations and relationships and invests the bulk of his cynicism here. The Doctor and Peri actually get along reasonably well, and Saward writes two things that are almost romantic by his standards: firstly, there’s the DJ (played by Alexei Sayle), who’s an awkward rock’n’roll nerd whose job is to play music, read letters from bereaved relatives, and provide news updates to the dead. Once the Daleks attack, he creates a ray gun that fires ‘a highly directional ultrasonic beam of rock and roll.’ Having Alexei Sayle in Doctor Who killing Daleks with a gun that fires music is, it goes without saying, fantastic.

Secondly, the Doctor actually helps when he enters this story. Given Davros’ revelation about where the galaxy’s food supply is actually coming from, the Doctor announcing there is a solution to the potential famine is quite refreshing. An Eric Saward story where the bad guys mostly kill each other in the crossfire and the Doctor steps into the gap with a better alternative? In this economy? Absolutely I’ll take it.

8. Warriors’ Gate (Season 18, 1980)

Written by Stephen Gallagher. Directed by Paul Joyce.

In which the Doctor, Romana, K9 and Adric find themselves trapped in a void between dimensions, alongside a slaver ship carrying Tharils – leonine time-sensitives who seem at home in this void.

An incredibly ambitious production, ‘Warriors’ Gate’ was Stephen Gallagher’s first TV script. Inspired by Australian indigenous beliefs, French surrealism and classic Science Fiction novels. The scripts were overhauled by director Paul Joyce and script editor Christopher H. Bidmead as they weren’t deemed suitable for a TV production. Making the story was fraught, helping convince Bidmead to leave the show and with Joyce never working for Doctor Who again.

The result is unique in Doctor Who. Nothing else looks and feels like this: a hard sci-fi tale about slave trading and the banality of evil, but taking place in a void between dimensions with temporal and physical journeys across the titular gateway. The nearest comparison would be the vibe of ‘Ghostlight’ with the visuals of Episode 1 of ‘The Mind Robber’. It’s entertainingly strange.

There’s a clinical edge to this story despite its ventures into the surreal, the result approaching Samuel Beckett writing an episode of Star Trek. This tone means Romana and K9’s leaving scene is somewhat muted, but there’s a steady stream of deadpan comedy throughout.

Rorvik is a fascinatingly banal villain, cut from similar cloth to Krennic from Rogue One – a small man who has found himself wielding impossible power and cruelty with the air of someone managing a photocopying company in Grantham. Also interesting are the Tharils: not least because of their journey from slavers to slaves to freedom, but the concept of a time sensitive race who could travel through the vortex unaided is a fascinating one. Overall ‘Warriors’ Gate’ is almost symbolist or impressionist in its approach, but even if you’re not fully aware what is going on it’s still fun to watch. Such a shame that it was apparently a terrible production to be part of.

7. Kinda (Season 19, 1982)

Written by Christopher Bailey. Directed by Peter Grimwade.

In which the Doctor, Adric and Tegan explore Deva Loka and find a human survey team at their wits’ end. Tegan, meanwhile, gets possessed by the Mara – an evil creature of the subconscious trying to manifest in the physical world.

There are two main positives to this story: one is the richly layered depictions of men in conflict with the natural world, and how their sense of superiority and masculinity ultimately harms them, and the other is that it’s always funny when the Doctor is rude to Adric.

The horror in this story mostly comes from the character of Hindle, played by The Bill stalwart Simon Rouse. Hindle is dismissed and patronised by his superior, the bluff and crass relic Sanders, and starts to regress to a childlike state full of tantrums and childlike logic (‘You can’t mend people can you?’). The problem here is that he’s the security officer and has access to a lot of weapons (‘Fire and acid, acid and fire’), which makes things rather unnerving.

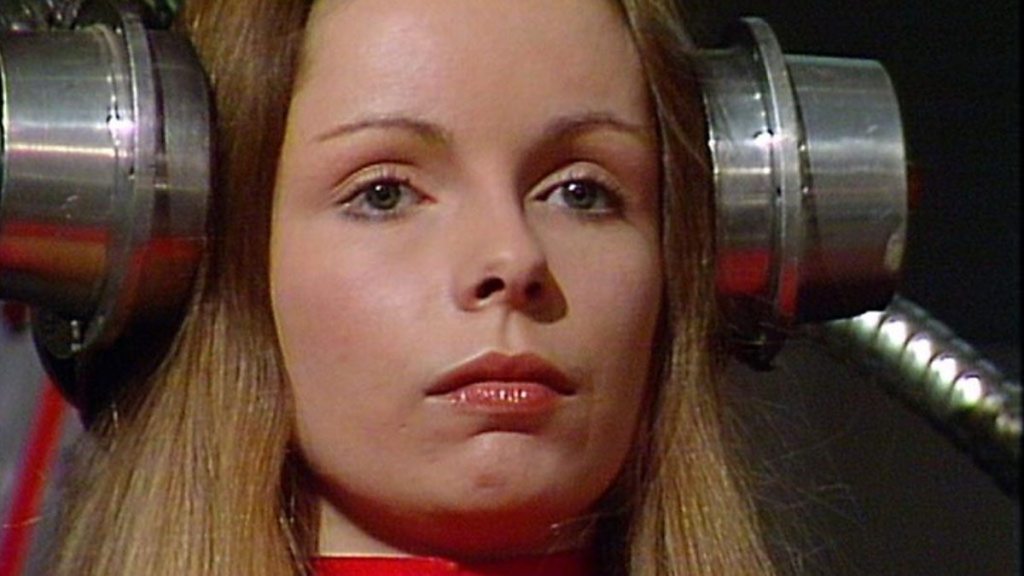

Tegan’s possession is unsettling too. In a dark void we see warped reflections of the Doctor, Nyssa, Adric and the TARDIS, speaking both incomprehensibly and extremely confidently. Their mind games unsettle Tegan to the point of agreeing to being taken over purely to escape from them. Her possession doesn’t last for long, which is disappointing, because Janet Fielding is much better at acting possessed than the bloke from That’s Life! It’s noticeable that the Doctor’s behaviour towards Tegan after she’s possessed is not entirely comforting, giving some credence to Tegan’s dream-version of the Doctor being irritating and unhelpful.

The story was written for the Fourth Doctor, and Davison filters this dialogue through his own sensibilities. It’s something that his stories could have stood to have had a little more of, this deadpan bemusement that people didn’t know when to take seriously. It helps define the more serious moments more clearly. ‘Kinda’ has a similar quality, it’s both playful and deadly serious and childlike and horrifying all at once. Like ‘Curse of Fenric’ it builds up clues towards a finale monster reveal. It’s less densely packed than Fenric but feels less random in its journeying. This story’s sequel ‘Snakedance’ is better structured but loses some of the intensity and chaos that makes this so fun to watch.

6. Survival (Season 26, 1989)

Written by Rona Munro. Directed by Alan Wareing.

In which the Doctor and Ace return to Perivale to see what Ace’s friends are up to, and discover they’ve been hunted by Cheetah People from another planet, one that emits an animalistic force that has ensnared the Master.

There was a cruel irony in the last story of the original run being called ‘Survival’, now, it’s like a beacon. While Russell T. Davies would have brought the show back in the same way without this story, it’s clear how much connective tissue there is and that the approach of the late Eighties deserves plaudits. There’s also a nice mirror of ‘An Unearthly Child’ here, both stories touching on nuclear power and Mutually Assured Destruction in a contemporary London setting.

‘Survival’ stands out in Season 26 by virtue of having the Doctor not having a pre-established plan, and indeed asking Ace permission before attempting to do something dangerous. It also features monsters in suburbia, in council estates, and homes in on the effects of political ideologies on young adults: the frequent references to survival of the fittest connecting the then-Conservative government to the instincts of the Cheetah People to hunt, prey on and play with people. This is leavened with some nice one-liners (‘We thought you’d died. That or gone to Birmingham’ and ‘Do you know any nice people?’ spring to mind).

It’s no coincidence that the first story written solely by a woman since 1983’s ‘Enlightenment’ is a great story for Ace, moving her away from the BBC version of a working class teenager towards a young woman who actually has a foot in the real world. Sophie Aldred responds with her best performance. Anthony Ainley also does well playing a broken and savage version of the Master, giving his faintly tragic version of the character something other than ludicrous preening to do.

‘Survival’ was never intended as a full stop, and indeed the connective tissue to the start of Doctor Who and the restart in 2005 makes it an effective ellipsis. Making this story without the knowledge that the show was coming to a long but temporary halt means that the Doctor and Ace head off to further adventures, which was the best thing that could have happened in the circumstances.

5. The Keeper of Traken (Season 18, 1980)

Written by Johnny Byrne. Directed by John Black.

In which a fairy tale planet where ‘evil just shrivels up and dies’ starts to shrivel up and die, and the dying Keeper brings the Doctor in to help.

The beginning of the end for the Fourth Doctor sees the Master return after four years, and the big thematic concern of entropy that runs through ‘Logopolis’ is introduced here. Traken is on the wane, run by a fading Keeper and a group of inept and bickering Consuls. The Master, staying in his TARDIS which is disguised as a calcified statue, exacerbates this collapse in an interesting way: as part of a typically convoluted plan, he preys on a very human weakness.

Kassia is recently married to Tremas, who is considered a strong candidate to be the next Keeper. The Keeper of Traken is connected to a vast power source and oversees the planet, maintaining harmony at the cost of total dedication to their task. Kassia is understandably conflicted at the prospect of losing her new husband to this job, and the Master exploits this, turning Kassia into his pawn and giving her the role of the evil Step-Mother in this fairy tale realm.

If, for you, a key part of the appeal of Doctor Who is in its combinations of ideas, then this story is very rich. While not intended as political, there’s something to latch onto in its depiction of a failing civilisation being exploited by fear. The mere presence of the Master manifests as societal decay. There’s a mash-up of fairy tale and science-fiction tropes, answering the question of what it would take to maintain paradise with ‘a lifetime of dedication’, and there’s a burgeoning sense of drama borne out by Tom Baker’s performance, always able to suddenly take things deadly seriously and convey the high stakes of the situation.

What there isn’t, given the story hinges on it, is a stronger grounding in emotional truth. While Kassia’s love and fear are exploited, Tremas doesn’t actually seem too bothered by his wife’s corruption and murder. Doctor Who in the Eighties was not a show burdened by emotional realism, even on a perfunctory level, and this would be a significant factor in its own weakening and decay.

4. The Curse of Fenric (Season 26, 1989)

Written by Ian Briggs. Directed by Nicholas Mallett.

In which the Doctor and Ace find themselves at a coastal army base in World War Two, with Russians on the prowl and a top-secret decoding device at the ready, but everything is churning: the sea, the people, the land…

You know when someone has a band they really like and you just do not get it? But you give them a go. And then another go. And then a few more goes. And then finally, unexpectedly, you get it. You understand. You realise they are exactly as great as your friend said.

That, for me, was Pavement. But also ‘The Curse of Fenric’, a story that took about four viewings to appreciate. Andrew Cartmel’s approach to script editing is very ideas-heavy, but not so great on structure. This over-running story is dense with interconnecting concepts and powerful haunting moments. It also teeters over into melodramatic outbursts at times, and the cutting for the ending doesn’t quite convey the sense of chaos the production is going for. But also it’s got Nicholas Parsons fighting vampires in it. And he’s playing a broken man who is losing his faith, unable to maintain it in the face of a war where his side are bombing and killing innocents, and the vampires – teenage evacuees – are dragging his soul towards theirs by claiming they were doomed to their fate from birth.

Conversely a Russian soldier wards off vampires successfully through his faith in the revolution, and in one incredible moment, the Doctor wards them off by muttering the names of his companions. Also these vampires are actually mutated humans from an alternate future timeline (like the Dregs from ‘Orphan 55’ but done as a subplot in a bigger story) with the last of them brought back through time to Transylvania to inspire vampire myths and Bram Stoker.

Said it was dense with ideas didn’t I? And we haven’t even got to the main plot yet (an ancient evil entity that has history with the Doctor has put an incredibly long-term plan into action, and the Doctor is trying to stop it from achieving fruition while also putting Ace through another big learning moment without telling her).

The opening few episodes are a rapid back and forth between locations, adding kindling to the story until the cliffhanger of Part 3 where everything ignites. This is part of the reason the story can be hard to get into, there’s a lot of set up in terms of clues and McGuffins and getting the building block in place. Some of this is thematic, some of it is bringing the monsters into place for the finale. It’s a story that rewards repeat viewings because the final episode ties everything together, so foreknowledge of what’s happening when the building blocks are being put in place helps.

And this continues the sense of building a more mythic version of the Doctor started by ‘Remembrance of the Daleks’, establishing another long-term conflict that refers back to unseen events (the novelisation of this story also goes into more detail). Concepts like the scene mentioned above where the Doctor’s faith in his companions add to this, the sense of a character using their past to add new facets. As Ace’s creator Ian Briggs also brings out new things in her character, some more weirdly than others, but overall this is a fascinating and multi-layered script in which the Doctor is essentially fighting a demon for his companion’s free will, so hell yes to that.

3. Enlightenment (Season 20, 1983)

Written by Barbara Clegg. Directed by Fiona Cumming.

In which the Doctor, Tegan and Turlough arrive on an Edwardian yacht about to take part in a race, while Turlough attempts to renege on his deal with the Black Guardian to kill the Doctor.

Script Editor Eric Saward knew Barbara Clegg from working in radio, and Clegg’s ideas were influenced by sun particles, the book of Genesis, and her richer relatives being dicks to her poorer relatives at parties. From this she developed the idea of the Eternals – a race of immortals who find non-immortals entertaining, racing sailing ships through space using solar winds in a quest to win ‘Enlightenment’ or ‘the wisdom which knows all things’ and brings about your greatest desire.

‘Enlightenment’ is, tonally, a game of two halves. The opening half with its reveal of sailing ships in space, the explanation of the Eternals (delivered by Keith Barron in a fantastic performance) and the First Mate Marriner becoming obsessed with Tegan in a clinical and discomforting way, is thoughtful and character driven. Also the Black Guardian is in it.

The second half, where Lynda Baron comes in as the pirate Captain Wrack (with Imagination singer Leee John as her first mate) means we’re suddenly on the verge of thigh slapping after every line. The weird energy from this clash of acting styles actually works, even with John offering some of the most relaxed line readings in the history of the show. Given a lot of Episode 3 is a reception onboard Wrack’s ship, the contrasts and awkward moments are ideal.

Rarely for a Fifth Doctor story his companions actually react with appropriate horror to what’s happening to them, with Tegan noticeably upset by Marriner’s interest in her and the casual way Eternals invade her mind; Turlough, meanwhile, prefers to throw himself off the ship rather than continue to serve the Black Guardian. When he’s given the gift of Enlightenment at the story’s climax he gets his wish to no longer be in thrall to Valentine Dyall’s bizarre antagonist. Through this darts Peter Davison’s Doctor, torn between being insulted (‘You are a Time Lord. Are there lords in such a small domain?’) and curious, furious and occasionally remembering to be sympathetic to Tegan. This a story where a Doctor who finds it difficult to assert himself works, given the Eternals’ power, and Davison’s Doctor always feels like someone being pulled in different directions.

2. Remembrance of the Daleks (Season 25, 1988)

Written by Ben Aaronovitch. Directed by Andrew Morgan.

In which Ace and the Doctor arrive in London in 1963, where two factions of Daleks are fighting it out over a secret the Doctor left behind on his last visit.

‘Remembrance of the Daleks’ is a lot of things. It’s the beginning of the McCoy era scratching at the veneer of key moments of the show’s history, here finding fascism within the precursor to UNIT (before going on to look at the show’s fondness for the Victorian/Edwardian era and aesthetic and the savagery of the Master). It’s a Dalek story that delivers satisfying action sequences, but also remembers to actually be about something (there’s the story of the Daleks trying to steal a McGuffin, but the story’s actually about the dislike for the unlike and how it smuggles itself into the everyday). It’s a story made with renewed confidence, the clever script matched by a very solid production.

It’s also significant in that it’s the first story to suggest the Doctor as something mythic.

Previously the character was, irrespective of how many continuity references were on screen, essentially just an erratic explorer who didn’t want to ever go home. That had been the backstory for over a decade. Here we get the first hints of something more (the ‘Cartmel Masterplan’ to reveal the Doctor’s origins as mysterious third founding figure of Time Lord society), but that’s not what would actually be built on in the future. Not only is the Doctor actively trying to rid the universe of its greatest threats, but there’s a sense of the universe suddenly recognising this recurring figure.

The novelisation of this story (which is also fantastic, by the way) mentions the Daleks’ nickname for the Doctor as the Ka Faraq Gatri (or ‘Destroyer of Worlds’, which was prescient of them), and this would build into the ‘Oncoming Storm’ idea used in the 2005 TV revival (invented by Paul Cornell for his novel ‘Love and War’). On TV, this manifests itself in the suddenly driven character who can reduce a Dalek to dust with his words, who arrives with a plan and plays on his reputation to trick Davros into destroying Skaro. It’s a shocking moment that means the character – more than hints about a mysterious past – has expanded their capability.

1. The Caves of Androzani (Season 21, 1984)

Written by Robert Holmes. Directed by Graeme Harper.

In which the Doctor and his new companion Peri land on Androzani Minor and manage to get fatally infected, imprisoned by both sides in a gun-running dispute, accidentally cause the downfall of a government, and get quite a lot of mud on themselves.

After a near miss with ‘The Five Doctors’, Script Editor Eric Saward finally managed to bring former Script Editor Robert Holmes back to the show. Having been put off by the anniversary story’s shopping list, the only thing Holmes had to do here was regenerate the Fifth Doctor at the story’s end, giving him free rein otherwise. ‘Androzani’ bears a slight resemblance to Holmes’ last script (1978/79’s ‘The Power of Kroll’) with the presence of gun smuggling on a backwater planet, but free from the Key to Time format and the requirement to have the show’s biggest monster (Kroll is a giant squid-like creature) Holmes returns to venal yet powerful politicians (‘Carnival of Monsters’, ‘The Deadly Assassin’, ‘The Sunmakers’) and disfigured characters hiding in the shadows (‘The Deadly Assassin’, ‘Talons of Weng-Chieng’).

Here, Sharaz Jek is not simply a monster. He’s a tragic Phantom of the Opera style character, whose goals occasionally threaten the Doctor and Peri but also occasionally align. Indeed, he’s a lot more sympathetic than the hapless Chellak, the army general trying to stop Jek from interfering in the trade of spectrox (a drug that can slow down the effects of ageing).

Businessman Morgus has paid for the army to stop Jek, but is also hiring mercenaries to supply Jek with weapons: this forces the price of spectrox up and makes him wealthier. Jek may be extremely intense, amoral and driven by vengeance, but he’s comparatively reasonable compared to most of the other characters. This is something of a turnaround from Holmes’ earlier stories where the Doctor would work with the army or defeat the disfigured villain: here the Doctor just wants to get away, but it’s a significant development in Holmes’ writing that he inverts the standard roles of these characters.

What Holmes does in pitting the Doctor against this ensemble of mostly terrible people is provide a perfect ending for this Doctor. With Eric Saward’s influence, deliberate or otherwise, pushing the stories in more cynical and violent directions (with Tegan’s departure as a result of this, and specifically the Doctor taking up arms), we have the Doctor finally stopping reacting to this sort of story with further violence, and instead simply remove himself and Peri as soon as possible. However, as they’re both dying from raw spectrox poisoning this is easier said than done, but in saving Peri – who he’s only just met and, to be honest, doesn’t seem to like that much – this Doctor is finally making a stand with his own values. Peter Davison rises to the challenge of playing this incredibly driven and determined – yet still fatally vulnerable – Doctor. It’s an astonishing performance, matched by the direction of then-newcomer Graeme Harper.

Harper had worked on the show for a while (indeed, he’d directed parts of ‘Warriors’ Gate’ due to the behind-the-scenes troubles there), but this was his first story officially in the Director’s chair. He directed the hell out of it, to the extent that whole scenes had to be abandoned because he was doing so much. The way it was shot and the choices made in the production give it a noticeably different feel to, say, ‘Frontios’ – produced earlier in the same season, also featuring underground caves and a perfectly good story in its own right, but it simply doesn’t have the energy and dynamism that ‘Androzani’ does.

Look at the ending of Part 3: Doctor Who is exciting sometimes, sure, but rarely with this intensity. The camerawork, the cutting between characters, the rising volume of acting and engines, the increasingly close-close ups…all of this was rare for Doctor Who in the Eighties, with the show still filmed in a similarly theatrical setup to the Sixties. The end result is undeniably thrilling, no matter how many times you watch it.