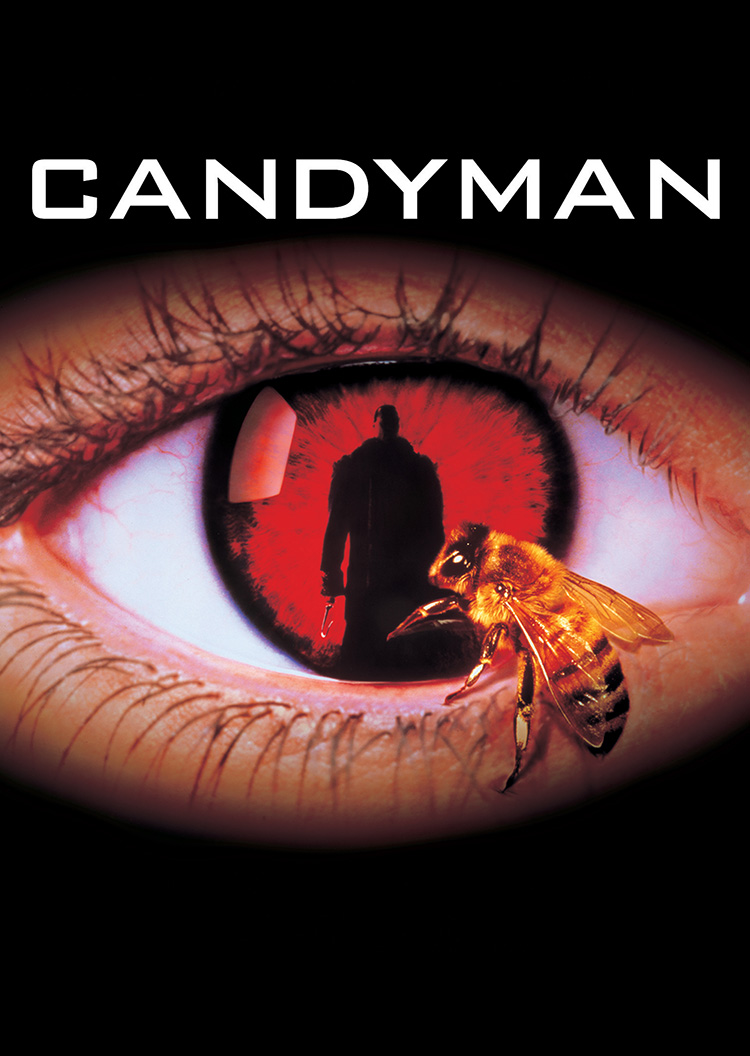

“Stand in front of the mirror and say his name five times…” Back in 1992 the horror genre had a brand new classic in its repertoire with Candyman, the story of a university student (Helen, played by Virginia Madsen) completing her thesis on urban legends, which leads her to the legend of the ‘Candyman’ (played by Tony Todd), the ghost of an African-American artist and the son of a slave who was murdered in the late 19th century for his relationship with the daughter of a wealthy white man.

Based on Clive Barker’s short story ‘The Forbidden’, the movie was written and directed by Bernard Rose after a chance meeting between Rose and Barker where the latter gave him his blessing to turn the story into a feature film. A critical success when it was released and just like the film’s central urban legend, the legacy of Candyman has endured, spawning two sequels and a recent ‘requal’ from Nia DaCosta.

We go back to back to where it all began with Bernard Rose to discuss the Candyman legacy, his thoughts on the latest addition to the franchise and working with bees…

So your journey with Candyman started with a chance meet-up with Clive Barker…

I vaguely knew Clive. I’d met him a couple of times when he was doing Nightbreed at Pinewood. I read the story, I thought it was a really good story and asked him if I could pitch it as a project and he said yes, and the first place I went to bought it so it was kind of easy. It doesn’t always work like that!

That’s pretty handy…

Haha I think people recognised it as something where it was potentially commercial. They weren’t wrong!

What was it about that short story that made you want to turn it into a feature?

I just really like the central idea that there was a monster that only existed while people believed in him. And if their belief was withdrawn, he would be in trouble.

I thought it was kind of a parable for the religious urges of human beings and I thought that it has some accuracy to it. I also thought it was a fun thing to do as a horror film, to have a monster where the only way he can fight back to save himself is to kill people so they believe in him more. Which is pretty much like all religions really. It always comes down to killing in the end, doesn’t it?

Then the thing that really interested me on top of that was when we changed the setting to Chicago and that racial element came in, which I think made it a lot more interesting. But the beats of the story come from the short story.

The original short story was set in Liverpool, why did you change the setting to Chicago?

We didn’t want to do the film in the UK, partly because Clive had had problems with Hellraiser. In that period these things tended to be funded by international video distributors and if films had too much of an ethnically accurate UK setting they were complaining that they couldn’t understand the dialogue!

Really?!

Oh God, that hasn’t gone away. People think it has, but it hasn’t really. It’s always been the case.

When sound in film first started in the 1930s, no one in England had ever heard American accents before and they couldn’t understand what people said.

When you think about it, there was no TV and they couldn’t hear the radio broadcasts. It wasn’t the age of mass tourism and certainly not mass transatlantic tourism. So they’d never heard Americans, especially things like Scarface where they’re gangsters or 42nd Street where they were speaking with New York accents. They had no idea what they were saying.

That was why the studios in response to that invented a thing called the transatlantic accent, which was actually perfected by Cary Grant. He was actually English but he kind of came up I think, in collaboration with Katharine Hepburn, with this very clipped very enunciated way of talking, which a lot of Thirties films adopted for that specific reason.

But in the other direction, it was a much bigger problem because eventually, quite quickly actually, the English audiences adjusted to American accents and so they could hear them but the other way around has never happened.

If you think about the Nineties British films that were hits in North America, they didn’t tend to have regional accents, and films like for example, Trainspotting I think was released with subtitles.

What was it like shooting in Cabrini-Green in Chicago? Was the estate’s representation in the film accurate?

Yeah it was a pretty accurate representation. It’s been knocked down since and it’s all been gentrified, which is documented in the recent film of course. But yeah, I mean it was pretty much what I saw there was what it was like. It was quite shocking really.

But the thing is, Clive’s story was set in somewhere in Kirby which was full of modernist housing projects and had become very rundown. So I didn’t really change what happened in terms of the people and the things there. I didn’t change it that much when we changed the setting. It was just what people looked like and the actual buildings. So you could say the same things were going on in bad housing estates in the UK too.

The film obviously does engage with the whole thing of the failure of the modernist public housing projects and how they very quickly became very frightening and threatening spaces. Architecturally, a lot of them are actually quite creative and interesting. That’s another thing that was definitely in the film, how in other contexts, the buildings that were maintained and properly secured, people desired living in them and that’s absolutely still true.

Candyman is still very relevant. What do you think it is about the movie that still captures people today?

It’s very interesting because it was successful when it came out. Probably a little more successful than they admitted actually.

It was successful, but it wasn’t taken particularly seriously. The Nineties were kind of a low point for horror films. In the Eighties we’d had the slasher boom, and the slasher boom had degenerated into too many sequels.

The first iterations of Eighties films were wonderful, but they degenerated into pastiche, which I think was the problem. At least by the early Nineties, they had. So it was a low point and it was at a point where people in the studio would say, ‘don’t call it a horror film, call it a psychological thriller’. They’d do anything to avoid you saying the word ‘horror’ which I think is the same thing as now when they use this ghastly phrase ‘elevated horror’. When they say elevated horror, I think what they mean is that it’s not frightening [haha]!

Certainly my intention with Candyman was always to make it very frightening and I think part of why it lasts is I think most horror films disappoint on that basic level.

What was it like being part of the horror genre in the Nineties?

Well people didn’t used to watch horror films. I mean, I think that year, Coppola’s Dracula came out, but it wasn’t marketed as a horror film, it was marketed as a period romance which it kind of was, to be honest. But it’s Dracula, if that’s not a horror film I don’t really know what it is! I really liked that film, but it was obviously a very different kind of film – big-budget and glossy. I was making something that was quite realistic in terms of its art direction and details. So it was different. It wasn’t the norm of what was going on at that period. It was unusual.

It was the era where glossy dramas were fashionable. Which is why the Dracula thing was perfect because they could market it as that, not as a horror film.

A lot of the practical effects of Candyman still hold up today. How involved were you with that process?

The big thing was the bees. In the film all the bees you see are living, breathing bees, they’re not computer generated on any level. They are real bees. I think it’s very obvious when you see the film that they’re moving about and going in the direction they feel like going. They’re not predetermined by somebody with a mouse that’s clicking off a storyboard, and I think that made a huge difference.

You would not be allowed to do that now I don’t think. It wasn’t dangerous per se, but it was potentially harmful. I mean everybody in those scenes were stung at least once.

We’d heard a rumour that Tony Todd actually had real bees in his mouth…

Oh, yes! We had a wrangler that was an entomology professor who had synthesised queen bee venom and if he applied this queen bee venom to you, the bees would regard you as a queen, and protect you rather than stinging you. That was the idea. I mean, it certainly worked to a very large degree. We had, I think three colonies up on the roof. Bees don’t live very long so we had them all living up there and they were being hatched all the time. For the first 24 hours of their life, a worker bee’s venom is immature. But it’s the second 24 hours that they have mature stingers. So we were using immature bees. I’m sure the odd one with the fake ID slipped in though…

I think everybody was tested to see if they were allergic because obviously bee stings, while unpleasant, are not dangerous unless you’re allergic and then you could go into anaphylactic shock but we had nurses with the epinephrine standing by in case somebody got stung.

The two central performances from Virginia Madsen and Tony Todd are pretty great…

Yes, they both were great in the movie in very different ways. I think the film, I wouldn’t say ruined, but it has severely affected Tony’s life in a way that’s kind of interesting and that to this day, I think pretty much anywhere he goes he’s the Candyman.

He does a lot of other things. He’s a very wonderful actor, Tony. I have a film actually, that he and I made in 2020 called Travelling Light where he plays the lead and he’s very wonderful in it. He’s a great actor. It’s always that thing, nobody wants to be typecast. But on the other hand, if that doesn’t happen to you at some point, then probably no one knows who you are either. So it’s a difficult one.

There’s a bit of romantic tension between the two. Was that always the intention?

He’s absolutely a lover not a killer. That was always the part. He’s not looking to kill anyone. He only kills you if you ask him basically. He’s a consensual killer!

What did you think of the recent Candyman film?

I think it’s great because if anything you do, people are still caring about enough to make another movie 30 years later, that’s great. Especially if it’s somebody with as much talent as Jordan Peele, and also I think that him engaging with it was great, because at the time when the film came out, it was, I think, weirdly more controversial than it is now.

I think it’s been kind of accepted how its themes and things work into the black experience in America and I think Jordan’s film, to some degree, codified that, so I think that was really interesting, and was really good. He needs to make some more.

Candyman does deal with some very important themes. What is it about horror that provides a good platform to explore such issues?

I think that horror has always been a genre where people can confront their fears. And you can tell a lot about society by what they’re afraid of. Even in literature in the 19th century, a lot of the things that people still read and still cherish were in the horror genre, everything from Mary Shelley to Edgar Allan Poe to Bram Stoker. It’s interesting how those books are still very much in the mainstream.

The 19th century was really the century where the genre really took off. Partly because it was a century essentially obsessed with death and the fear of death. They were mechanising the world and I think it frightened people. So it was a mixture of horror and sci fi. I think the genres are always a little bit more blurred than people like to think. As much as if you say the first horror book is Frankenstein, you can also say the first sci-fi book is Frankenstein. So what it is depends on how you look at it…

Candyman is out on 4K now from Arrow Video