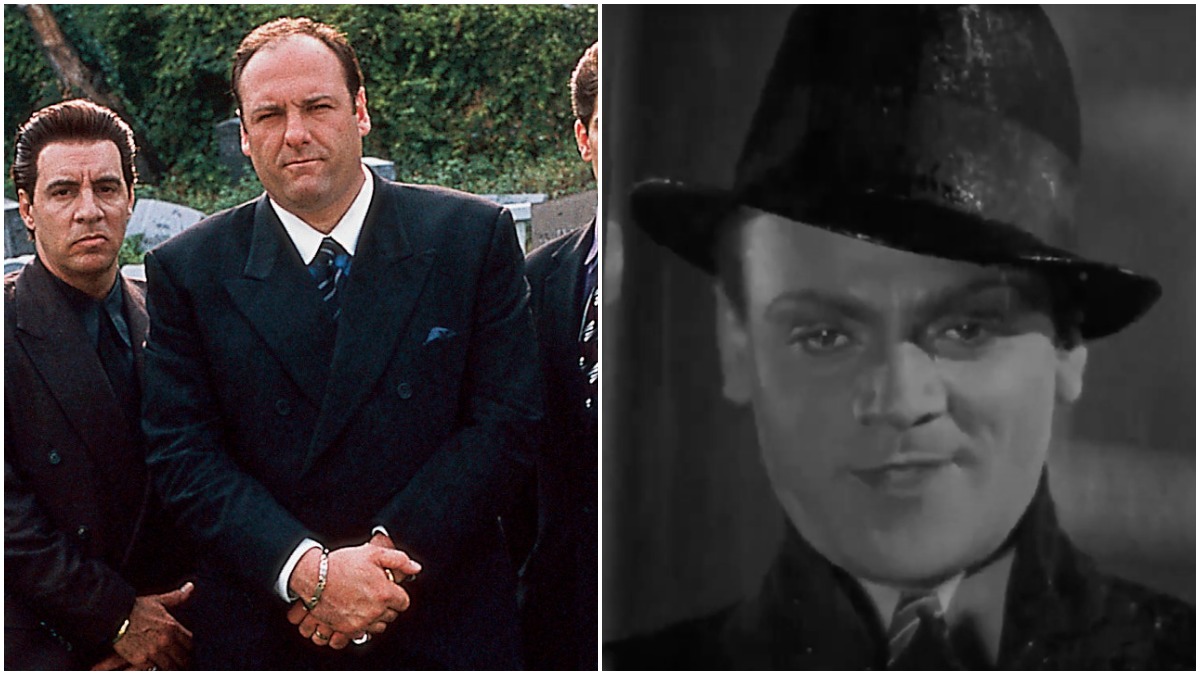

HBO’s crime family series The Sopranos wore its gangster roots like the wingtips on the hair of Paulie Walnuts (Tony Sirico). You could count on Silvio Dante (Steven van Zandt) to get pulled back into doing his Al Pacino impression from The Godfather, Part III, or punching Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) in slow motion when the music from Raging Bull comes on a jukebox. Half the cast was in Goodfellas, and Tony often stays up late watching mob movie classics on TV. This is repeated in the prequel feature film, The Many Saints of Newark, when a young Tony is watching Edward G. Robinson and Humphrey Bogart face off in Key Largo. But it is gangster genre icon James Cagney who looms largest over the series.

On The Sopranos, Paulie often opens friendly chats with the phrase, “What do you hear? What do you say,” which was the street salutation of Rocky Sullivan, the mug Cagney played in Michael Curtiz’s 1938 gangster movie classic, Angels with Dirty Faces. Like Sullivan’s relationship with the Dead End kids in the film, The Many Saints of Newark sees Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola) mentor both a young Paulie and a teenage Tony (Michael Gandolfini), who’s got an East Side Kids gang of his own. Sirico paid Cagney further tribute by the way Paulie holds his pinky ring in the series.

In the season 3 episode, “Fortunate Son,” Tony is watching William Wellman’s 1931 gangster genre touchstone, The Public Enemy, when he has a disheartening heart-to-heart with his daughter Meadow’s new boyfriend Noah. The film later brings tears in his eyes when the loving relationship between Cagney’s Tommy Powers and his doting mother touches a nerve in Tony, remembering his dead mother Livia (Nancy Marchand). In a recent interview, Chase said his youthful nighttime viewing was The Untouchables TV series, which he watched with his father every Thursday night. “I only watched it for the mobsters, because they had the really great roles, very theatrical and active and murderous,” Chase told THR.

But the most theatrical and active play on Chase’s imagination was The Public Enemy. “I saw that long before The Untouchables,” Chase said. “They used to have a thing in the New York metropolitan area called Million Dollar Movie, and they played the same movie for five days, right in a row, at 8 o’clock. And if you were interested in film, which I didn’t realize I was, it was great, because you could watch the same movie, and if you’d miss something, you could go back and you could study it, in a way. It was fantastic. And I saw that movie there. I was probably eight or nine.”

Charismatic villains in more modern crime films like Bonnie and Clyde, Goodfellas, and New Jack City owe a great deal to The Public Enemy. Cagney’s Tommy Powers was unapologetic, explosive, and as loose a cannon as film knew at the time. He didn’t have the reasoning powers of puppet masters like Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone or Marlon Brando’s Don Corleone in The Godfather. He had the brute force and recklessness of Robert De Niro’s Johnny Boy in Mean Streets. Powers didn’t care how the world saw him, and had no patience for soft manipulations of the Hays Office or wily women. He wanted what was his, now, and if he got something he didn’t order he had no problem sending it back.

“There’s also a famous scene in that movie where he’s got a girlfriend,” Chase recalled, “and they are eating breakfast in this high-flying hotel, and she says, ‘I wish’ [about] something he wants. And he says, ‘I wish you was a wishing well so I could tie a bucket to you and sink you,’ which makes no sense. But then she says something and he picks up her grapefruit and smashes it into her face. It’s, strangely enough, one of the most famous scenes in movies.”

The scene where Cagney shoves the grapefruit into the face of Kitty (Mae Clarke, best known for playing Elizabeth in Universal’s 1931 horror movie Frankenstein) is brutal, harsh, ugly, and misogynist. It is also a distillation of the era’s street charisma that Cagney’s character is required to exude.

“They say it’s always the badasses who make a girl’s heart beat faster,” Epiphany Proudfoot (Lisa Bonet) says in Angel Heart, and Tommy Powers was the baddest ass of the early 1930s. Check out the scene where he gets fitted for slacks, and needs more room in the inseam.

The Godfather already put the squeeze on oranges, so The Sopranos got some juice from the grapefruit in its homages. In season 1, episode nine, it comes out that Junior Soprano (Dominic Chianese) has been spending time south of the border with his Boca Raton goomah, Bobbi Sanfillipo. The title of the installment is “Boca,” and it refers to Sanfillipo’s big mouth and what it’s been saying about where Junior’s loose lips have been. This is the episode which leads to the line “psychiatry and cunnilingus led us to this,” and Bobbi is the first casualty. It’s not lethal, but it is a bittersweet moment.

Like any organization which follows a code, there are always some poorly defined rules. Made men don’t kill other made men, they don’t sleep with each other’s wives, and don’t pleasure women orally. It’s not manly. Cagney was made to feel subservient in The Public Enemy, and lashed out with citrus. When Bobbi admits she may have let out Junior’s secret lovemaking talent, he smashes a pie in her face. The act is a final one, and it is passively violent and aggressively humiliating.

It seems like a big penance for a small sin, bragging on your lover’s prowess, but all Kitty did in The Public Enemy was tell Tommy he might not want to drink before breakfast. Gangsters don’t like to be told what to do, and it’s only a small taste of what he might unleash. “Public Enemy was the movie that started my love affair with the gangster movie,” Chase told the New York Times in 2001. “It really scared me. Especially at the end when Cagney falls through the door all wrapped up like a mummy.”

Chase is no stranger to memorable endings. His own ending to The Sopranos is most frightening in how it’s been challenged and rebuffed. The mystery and suspense of the scene is almost linoleum Gothic, and the abrupt cut to black remains the most jarring series finales in television history. Similarly, the ending of The Public Enemy was so unexpected and graphic, it could fit in Christopher Moltisanti’s “Cleaver,” the fictitious horror gore fest all the families produced.

“Oh, it’s fantastic, I mean, it scared the shit out of me,” Chase told THR. “Cagney played a guy named Tommy Powers who becomes a gangster, but he is very close to his mother, and his brother is like the hero of the family. And Tommy goes through a lot of things. But the ending, yeah: Tommy gets shot and he is in the hospital and he is bandaged like a mummy; you can see his face, but the rest of him is all bandaged. His mother and brother go home—they’ve been told Tom will be coming home in three days. His mother is fluffing up his pillows for him, singing along with a record, ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles,’ she’s all happy, a few pillow feathers are going around. His brother’s downstairs. There’s a knock on the door, and the brother opens it, and there’s a low shot of the door from the floor, as the door opens, and he’s standing there, Tommy, all wrapped in these bandages and a blanket. But then he falls forward into the lens—he’s dead. Oh, it was really a shock. And his mother is still singing up there.”

Chase actually brings out two very important takeaways The Sopranos glommed from The Public Enemy: the first is the playing of the popular tune, “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.” It is heard during the most brutal scene in the film. This was true on the streets when mob hits happened in night clubs or took collection money while car radio blasted, or when an enforcer might want to cover up the sounds of a beating. This was most memorably caught in Jimmy Breslin’s book, which became the film The Gang that Couldn’t Shoot Straight, where a mug feeds quarters into a jukebox and winds up putting on a soft Beatles song which is not loud enough to cover up the business at hand. Chase infused The Sopranos and The Many Saints of Newark with music, as did Martin Scorsese in his many crime pictures. They use hits to define the period, just like Wellman does in The Public Enemy.

The other point he makes is about the mother. Cagney’s gangsters had very interesting relationships with their mothers. In Angels with Dirty Faces, which also starred Bogart and Pat O’Brien, Cagney’s character cries for his momma on his way to the electric chair. In Raoul Walsh’s White Heat (1949), Cagney’s Cody Jarrett is the toughest mama’s boy you’d never want to run into. Whether he’s tearing up a prison cafeteria in her memory or shouting “Top of the world ma” in the gangster genre’s most incendiary ending, he remembers mama.

Tony is almost dismembered by his mama, Livia, who manipulates Junior into ordering a hit on his nephew which takes off a piece of Tony’s ear. ”I thought about Public Enemy because I remembered how the mother in that movie had been sweet to her son, just the opposite of Livia,” Chase told The Times. ”I thought about how that might affect Tony, and also how the gangster dies at the end and how he might be thinking about how a gangster’s life often ends in death.”

Livia is actually closer to the mother in Howard Hawks’ Scarface, which the Hays office called a “grasping virago, distinctly an Italian criminal type mother” which would bring “odium and shame upon his entire race,” in its threat to bar the film from distribution approval. Tony’s mother was a Machiavellian marvel.

The Sopranos also caught flak about its depiction of Italian-Americans and the ethnic cliché of Mafia families. That didn’t stop the Soprano family from inviting everyone to a family dinner every Sunday night for six years. They always served the choicest cuts, and always served classic endings.