Have you heard? If not, let Steven Moffat be the first to tell you: Whittaker’s Doctor is “going to fight THE WEEPING ANGELS!!”

Moffat, who invented the Weeping Angels, has every right to be proud of his creation. Few would dispute that the Weeping Angels are NuWho’s break-out monster. In a 2020 poll of scariest Who monsters of all time, the angels ran away with the vote. Modern viewers might not retreat behind the sofa anymore when the Daleks roll in, but “Blink” had people giving cemetery statues a nervous second look. There’s a delicious fright to the idea that an innocent stone statue might begin to move the moment you look away.

But the promised return of the Weeping Angels begs the question: are the Weeping Angels the kind of monster we want to see again and again? After all, some foods get better with age. Others just get stale.

Since “Blink”, the Weeping Angels have appeared numerous times, sometimes as the main villains and sometimes as, well, background furniture. But by the time the Statue of Liberty was revealed to be a Weeping Angel (“The Angels Take Manhattan“), something that had once been terrifying started to feel a bit . . . silly. Beyond breaking the established rules of the Weeping Angels—(to fans who wondered how the Statue of Liberty could move in the City That Never Sleeps, Moffat answered that “The Angels can do so many things”)—the Statue of Liberty angel broke the horror premise. The angels became not a thing waiting for you in the darkness behind your eyes, but in-your-face and obvious. And for a horror monster, that’s a problem.

At their core, the Weeping Angels belong to the horror genre. Certainly, they have aspects of sci-fi in that they are “quantum locked” and transport people back in time. But when you dig down into what actually makes the Weeping Angels successful, the reasons all belong to classic horror. They move when you’re not watching. They’re getting closer. They’re getting closer. “Don’t blink” is such a powerful phrase because it sounds so simple and yet is impossible. We know that everybody blinks in the end.

In their horror roots, the Weeping Angels have more in common with another Moffat monster, the Vashta Nerada, than they do with other Who regulars like the Daleks and Cybermen. To jog the memory, ‘Vashta Nerada’ were those piranha-like shadows that strip your flesh from your bones, introduced in “Silence in the Library”. Like the Weeping Angels, their capacity to frighten comes from their simplicity and ubiquity. Any shadow might be a killer shadow. And by the time you notice that you’ve acquired a second shadow, it’s too late.

The Weeping Angels and Vashta Nerada aren’t the kind of monsters that require complicated lore to be effective. In fact, complicated lore would diminish their effectiveness, because at heart both are predators, intelligent, but not complex. Their reasons for killing are no more complex than the reasons a cat kills a mouse. You could hardly imagine a Weeping Angel story with the same plot-line as “Dalek,” in which a dalek absorbed some of Rose’s DNA and began to feel emotions, a feeling so distressing to it that it begged for its own execution.

Read more

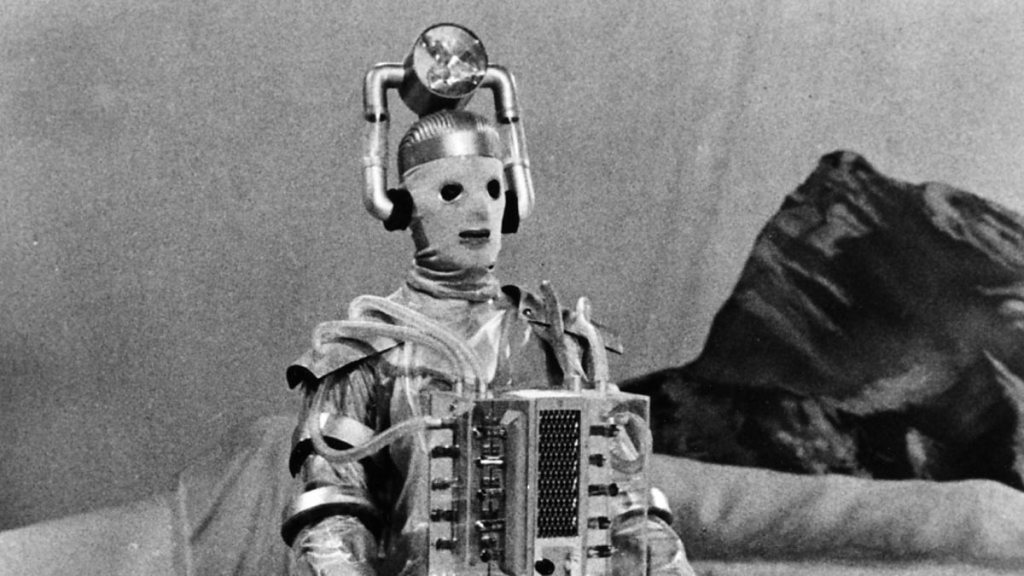

In fact, the Daleks and the Cybermen make for an interesting comparison. While at surface level they both might seem to have one-track minds bent on supremacy and world domination, we know that the Daleks suffer from pride and vanity, and that the Cybermen in most cases prefer conversion to murder. Because ultimately, the Daleks and Cybermen are monsters rooted in the sci-fi tradition. They are cyborgs, and their monstrous nature stems not from being purely alien and predatory to humans, as the Weeping Angels are, but from being humanity distorted.

The Cybermen were once like humans. In their introductory story, “The Tenth Planet,” a cyberman explains in his singsong voice that their home planet Mondas was the twin to Earth. But the humanoid inhabitants’ lives grew shorter and shorter with each generation, driving them to a cybernetic solution. In that story, humans initially appear to be the brutish and war-like ones, rejecting the Cybermen’s offer to bring them safely to Mondas and instead arming a nuclear warhead to destroy their planet—and likely irradiate most of Earth in the process. More frightening than the admittedly creepy original cybermen was the destructive potential of humanity. For the first few episodes we’re forced to wonder if maybe the Cybermen have a point about pitfalls of unbounded human emotion.

Similarly, in “The Daleks” (initially titled The Mutants), we meet the Daleks on their petrified, irradiated home planet, Skaro. Clearly something has gone badly wrong and we quickly learn that the Daleks have been shaped by neutronic war. The history of the Daleks becomes even richer in “Genesis of the Daleks,” where we meet the Daleks’ creator Davros and receive more context for the war on Skaro. We see the wriggling organic bodies of the Daleks and share the Doctor’s mixed pity and disgust. The story brings to the fore themes of mercy and sacrifice.

It’s telling that the first appearances of the Daleks and Cybermen revolve around their home planets and what drove them into becoming as they are. Fundamentally, they are monsters that require an explanation. The Weeping Angels don’t need that. They kill because it is their nature to kill; they kill to eat and live. We don’t need to know anything more to fear them. In contrast, for the Daleks and the Cybermen knowing where they come from is essential to what makes them monstrous. And this is exactly what makes them effective repeat monsters.

That’s not to say that the Daleks and Cyberman can’t be overused—the gratuitous Timelord-Cybermen from season 12 may come to mind as an example of such an abuse. But on the whole, the Daleks and Cybermen have the inherent potential to become more nuanced and compelling through multiple appearances because their appeal is rooted in emotions more complex than pure fright.

Now, just because the Weeping Angels have been motiveless horror antagonists thus far doesn’t mean they need to remain that way. In fact, before the Doctor Who spin-off Class was cancelled (spoiler ahead), it was revealed that the Weeping Angels were the villainous masterminds behind season one. For season two, showrunner Patrick Ness apparently planned to depict the Weeping Angel’s home planet and the civil war it experienced—a move that would potentially transform the Weeping Angels from silent assassins to complex characters. For some it may sound exciting to learn more about a favorite monster, but for others, the first reaction may be a wince, followed by a question: would the Weeping Angels really cast the same spell if we knew their full history? Without the horror, what’s the point?

In season 13, Chibnall could give the Weeping Angels new abilities or new lore. But what he’ll struggle to do is give them back the untarnished power to frighten that they wielded in their original appearance. Some of NuWho’s most successful episodes have tapped into the horror genre, and can do so again. Given the choice, I’d rather see Chibnall’s team come up with a monster capable of frightening and thrilling viewers the way “Blink” did back in 2007, rather than relying on the image of an angel to become, yet again, another angel.

Doctor Who Season 13 will air on BBC One and BBC America this autumn.