When Barrack Obama endorses a book, it’s big news, and there’s no denying that Cixin Liu’s The Three Body Problem garnered a lot of attention from the presidential book blogger’s comments when it was released back in 2008.

However, the real cultural significance of this book’s appearance was that the English translation went on to become the first Chinese SFF book to win a Hugo award for best novel. For the western world, there’s limited access to Chinese entertainment media. So the opportunity that the translation of The Three Body Problem provided to garner a new perspective on science fiction was devoured by the English-speaking world.

Now, in a bid to bring more of Cixin Liu’s work to a wider audience, Head of Zeus has orchestrated a mammoth international collaboration, bringing together over 25 writers and illustrators from 14 different countries to transform 15 of Cixin Liu’s stories into graphic novels.

What bleeds though in all the novels is Cixin Liu’s depiction of humanity. Each book takes an aspect of culture and what it means to humanity. Be that the value of art and how it can impact the world as seen in Sea Of Dreams or the value of education as a way to empower youth to escape the cycle of poverty in The Village Teacher.

While each story is thematic, the delivery is balanced, leaving space for the reader to digest and form their own judgements and opinions. Although these are all adaptations, bringing the stories to a whole new media of the graphic novel, there is a singular voice that permeates each of them. These are Cixin Liu’s stories. They feature fantastical feats of engineering and world-building that are both recognisable and distinctive while wrapping the heart of the story in a tenderness towards the fragile potential of humanity.

The whole project offers a fascinating insight to a ‘new’ author, with the graphic novels serving as a gateway drug to a traditionally inaccessible voice in the realm of SFF.

Here at SciFiNow we’ve pulled together a run down on the first few Cixin Liu’s stories to hit the shelves…

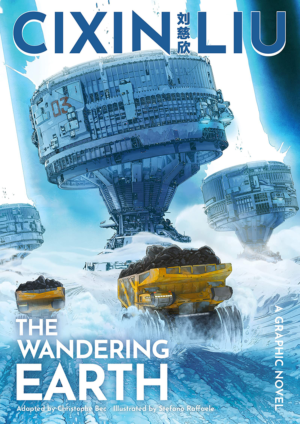

The Wandering Earth

Top of the pile is The Wandering Earth, adapted by Christophe Bec and illustrated by Stefano Raffaele. A book that’s already been turned into a movie (you can check it out on Netflix), the premise of The Wandering Earth suggests that the sun is dying and has begun a countdown timer to the end of days on Earth.

Whereas plenty of SFF stories would see humans either trying to fix the problem or build some sort of spaceship to try and evacuate a chosen few to save the species. The Wandering Earth smartly dispenses with these options and instead we see humanity coming together to turn the entire planet into an ark and embark on a journey of interstellar emigration.

The construction of thousands of enormous engines orientated on one side of the Earth are created as a way to physically push the Earth out of orbit, away from its dying sun and on a course for the closest feasible star, Proxima Centauri, 4.3 light years away.

The journey will take a thousand lifetimes, with each new generation on earth playing their part in the voyage, knowing they themselves will never reach their destination. But while on the journey, when most people are looking forward, eyes firmly on the target destination, there are those who are still looking backward at the sun and questioning if it really was dying. Did they really need to leave the solar system? As factions of rebels break out around the world, humanity must work to understand whether they fight them as conspiracy theorists, or side with them as anti-governmental protestors…

With an impressively unique premise, the human story at the heart of the novel is much more straightforward than the grand scale of the situation and follows a young couple as they fall in love and build a family only to see cracks appearing when they realise their values land on opposite side of the political spectrum. It’s a setup that is proven and familiar but plays out here with a starkly morbid realism that challenges the usual Hollywood fairy tale.

Against the grandiose explosions of Stano Raddaele’s artwork, Chriophe Bec’s adaptation brings an odd bluntness to the characters. The mood and feel of the book shares much of its tone with fellow countryman, Alexis (Matz) Nolent’s Snowpiercer series. The straightforwardness and practicality of decision-making make it hard to discern if the coldness of the characters is a cultural anomaly from the novel’s Chinese and French masters or if it is an intentional reflection on the morbid futility of the adventure.

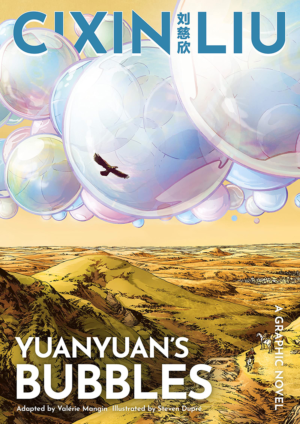

Yuanyuan’s Bubbles

TV comedy shows like Fresh Off The Boat or dramatic movies like The Farewell have brought focus to the challenges younger Asians can face as they try to engage with western societal values while still honouring and respecting their heritage and elders.

In the graphic novel adaptation of Cixin Liu’s Yuanyuan’s Bubbles, we see a new take on these conflicted family dynamics and the battle between tradition and the future.

Yuanyuan’s Bubbles appears, at first, like a rather simple, saccharine story centred around a young girl, Yuanyuan, whose only ambition in life is to blow the biggest bubbles in the world. The supposed immature naivety of Yuanyuan’s desires does not wain when she gets older. In pursuit of the dream to blow the biggest bubbles, she shows an affinity for science like her mother and starts to develop wonderous new chemical compositions that bring her accolades, wealth… and bubbles.

As Yuanyuan bounces from bigger to better things, her somewhat estranged father, the mayor of a poverty-ridden city, is left powerless, trying to nurse his already suffering city through an inhospitable drought. When he goes seeking support from his billionaire daughter, her focus remains only to blow bigger bubbles, deserting her father and leaving her hometown to the wolves of famine.

At its heart, this is a story about fathers, daughters and absent mothers. How the balance of respect and compassion shifts when dynamics change. A youthful and doting father is aged and embittered by the strain of a life spent trying to do the best he can for his children and his citizens. These sacrifices leave his daughter seemingly untouched by the burdens of society. She is able to live a perceptibly carefree life and society chooses to reward her selfish pursuits of satisfying her own happiness.

Buried in the subtext is a message that we should yearn for understanding and a balance of respect between generations and perspectives, which is a theme that can be seen in some of Cixin Liu’s other work. In Yuanyuan’s Bubbles however, the obstinate and singular focus that drives the story also serves to alienate the characters. The translation of the characters’ motivations seems incompressible and obfuscated; so much so that they don’t seem to carry enough weight. However, the writing and artwork work to sell the promise of wistful escapism while not shying away from harsh realities.

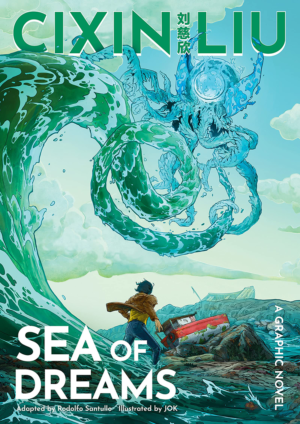

Sea of Dreams

Sea Of Dreams has one of the more out-there concepts that will work as a challenging thought experiment for ardent readers of philosophical sci-fi.

The story opens on a lowly engineer who likes to spend his spare time creating ice sculptures, and while he has supportive friends, there’s little recognition or appreciation of his art. That is until an alien being, a giant orb, appears in the sky to praise the frosty works. Referring to itself as a ‘Low Temperature Artist’, the orb sees a kinship with the novel’s protagonist, recognising them both as artists and proclaiming them colleagues.

Upon forming this collegial bond, the Low Temperature Artist is itself inspired to be creative and sets to work crafting its own ice sculpture. Whereas human ice sculptures are carved out of blocks of ice, the Low Temperature Artist has the ability to freeze water in any chosen form, allowing full freedom of expression. Unfortunately, the scale of the piece means that the orb is slowly and methodically draining the earth’s oceans of all its water. The orb is singular in its vision, claiming there is no higher purpose than art and disregards the pleas for humanity’s salvation as inconsequential. As the world is plunged into a global drought, it’s up to earth’s ice sculptor to try and reason with the orb and save the species.

Despite starting out with a slightly bizarre premise, that at first glance lacks any real hook, the novel unveils itself very quickly. The plot acts as window dressing to a more interesting conversation that sustains you long after the book concludes, developing as an analogous debate on the merit and value of art. The compromises and sacrifices that artists must choose to embrace and the lasting impact an artist can have on a world.

Sea Of Dreams could be perceived as somewhat semi-autobiographical, given Cixin Liu’s engineering background and his artistic expression through novels. While we hope that he’s never had to reason with giant space orbs, Seas of Dreams provides a fascinating insight into the journey of how someone comes to terms with their own place in the world, understanding his values as both an artist and as a member of a wider society.

Cixin Liu’s The Wandering Earth, Yuanyuan’s Bubbles and The Sea of Dreams are out now from Head Of Zeus.