The animal world infuses just about everything I write. Spiders, most notably, but also tigers, wolves, dogs and, most recently, bears…

Animals have been running through human narratives since before humans were human. We’ve always known that we shared the world with them. Modern life can’t divorce itself from that heritage, whether it’s Paw Patrol or the oft-repeated adages of how far you ever are from a rat. Drawing from this millennia-old inspirational well, animals sneak out of deep history into modern SF and fantasy narratives in all sorts of different ways.

Beasts in the mirror

Perhaps most obviously, there’s the story where everyone’s an animal. Sometimes they’re animal-shaped animals with a human window on the mind, such as in Watership Down (Adams) or The Animals of Farthing Wood (Dann) – those delightful childrens’ books that are so bludgeoningly traumatic when you actually read them. Other works anthropomorphise their animals. Jacques’ Redwall series is likely the best-known of these, with its medieval micescapades. Polansky’s The Builders marries the human-like animals of Redwall with the emotional punches of Watership Down. It’s a work gloriously unapologetic in its violence, nature not just red in tooth and claw but also axes, knives and six-shooters.

Beasts next door

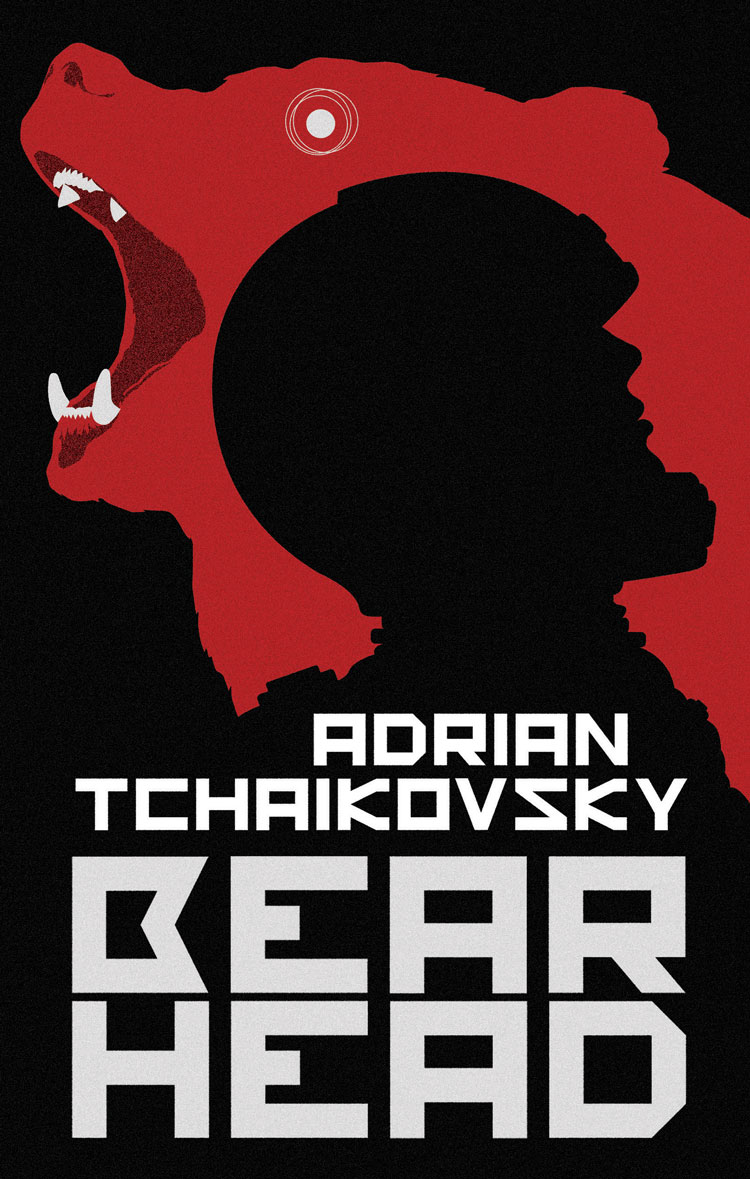

There are more than a few novels that bring up some kind of animal to a more or less equal state and have humans share the world with it. Pullman’s armoured bears in His Dark Materials are one of the better-known examples. (And I probably should try and drag bears into the conversation, given my own upcoming Bear Head). There are also the enigmatic Gullaime bird-people of Barker’s recent The Bone Ships, who have a hard time of it as slaves of the humans who need their wind-calling powers. And with the boot on the other digitigrade foot, humans are a surly underclass below the foppish, musketeer-y rats in Gentle’s marvellous Rats and Gargoyles.

Beasts at our side

Turning wolves into dogs was one of the first great moves our species made as we increased our agency in the world, and myths are full of pets, guards, informants and advisors in animal form. The animals which are more than animals, despite being visually just another mute beast. There’s the fox in Beagle’s The Innkeeper’s Song which has its own internal monologue and which, we slowly realise, is actually something huge and monstrous and terrifying except it just can’t be bothered with all that nonsense any more and would rather be a fox. Or, to stick with bears, there’s the human protagonist of Hardinge’s A Skinful of Shadows who acts as a vessel for ghosts – including the ghost of a confused and very angry bear that’s not ready to pass on just yet. Alternatively, of course, there’s the goat in Newman’s The Vagrant. Which is just a very ornery, stubborn and bloody-minded goat (much like, to go back to Hardinge, Sararcen the goose in Fly By Night) because sometimes just being a goat (or a goose) is enough.

Beasts as our skin

Turning into animals is another age-old trope, whether it’s Loki pulling a prank, Zeus’s frankly inappropriate love games or an American werewolf in London. In my Echoes of the Fall, everyone’s a shapechanger, and it shapes all aspects of their world. As a younger reader, the quintessential shapechanger for me was Ged in A Wizard of Earthsea. Le Guin sells the experience of being a bird and riding the winds so powerfully that, even now, ‘shapeshifting’ is still my default answer to the old ‘If you could have any superpower…’ question. Another writer who brings the experience to life is Pratchett in his Witches books, though there it’s ‘Borrowing’, riding the animal’s mind rather than actively taking on its shape. Still, the idea of being able to experience the world through different senses and in a different shape is a major driver for my own non-human characters, whether four-footed or eight.

Beasts as our Children

This is a mode of animalism that I dip into a lot: the sentient beasts that we, scientific humanity, might engender. Humans share the universe with the spiders (and various other things) in Children of Time, and humans engineer animal soldiers in Dogs of War, which Bear Head follows on from. And, if you’re doing this in SF, much of this is in the shadow of Brin’s Uplift books, where the deliberate anthropomorphising of animals is a major engine of the plot. Some of my absolute favourite engineered animals are from Gareth Powell, though. Ack-Ack Macaque presents a monkey that does exactly what it says on the tin, whilst finding time for a great deal of introspection about what it is to be a (gun-toting) simian in a human world. More recently, Powell gives us the Trouble Dog from Embers of War, a philosophical spacegoing warship with an AI that contains a lot of canine genetics – one of the most engaging creations of modern SF.

The Revenge of Nature

And if, in the very end, we can’t get on with the natural world, there’s always the chance that nature gets the last laugh. Jeff Vandermeer is a writer whose work is even more infused by the natural world than mine is, and he’s also a deeply committed environmentalist. His writing often presents nature as a cautionary tale: the terrible consequences of failing to respect the rest of the world. Whether it’s the monstrous kaiju-like bear in Borne or the entire ecology of Area X in the Southern Reach series, Vandermeer is a master at bringing unnatural nature into the lives of his readers. Going one step further than this is Peadar Ó Guilin in his novel The Call, where the twisted otherworld his protagonists are kidnapped into is inhabited by an entire hostile ecology that has been reverse-engineered into the animal from the human by its baleful faerie overlords. There is always, both writers seem to say, a bigger fish than mere humanity…

Bear Head by Adrian Tchaikovsky is out on 7 January.